Americans have always been fascinated by rich people.

We all want to be rich, after all; as someone once said, “The United States is a nation of temporarily distressed millionaires.” So, in lieu of actually being rich, we obsess about them. The rich used to be celebrities for no other reason than being rich. It’s always been interesting to me that in our so-called “classless” society (which was part of the point; no class privilege, everyone is the same in the eyes of the law) we obsess about the rich, we want to know everything about them, and we lap up gossip about them like a kitten with a bowl of cream. I am constantly amazed whenever I watch something or read something set in Great Britain, because that whole “royalty and nobility” thing is just so stupid and ludicrous (and indefensible) on its face that I don’t understand why Americans get so into it; the fascination with the not-very-interesting House of Windsor, for one. We fought not just one but two wars to rid ourselves of royalty and nobility…yet we can’t get enough of the British royals, or the so-called American aristocracy. (Generic we there, I could give a rat’s ass about the horse-faced inbred Windsors and their insane wealth, quite frankly.)

I wanted to be rich when I was a kid; I spent a lot of time in my youth fantasizing about being rich and famous and escaping my humdrum, everyday existence and becoming a celebrity of sorts with no idea of how to do so. I was intrigued by the rich and celebrities; I used to read People and Us regularly, always looked at the headlines on the tabloids at the grocery store, and used to always prefer watching movies and television programs about the rich. (Dynasty, anyone?) I loved trashy novels about obscenely wealthy (and inevitably perverted) society types and celebrities–Valley of the Dolls has always been a favorite of mine, along with all the others from that time period–Judith Krantz, Harold Robbins, Jackie Collins, Sidney Sheldon and all the knock-offs. I was a strange child, with all kinds of things going on in my head and so many voices talking to me and my attention definitely had an extraordinary deficit; I always referred to it as the “buzzing.” The only time I could ever truly focus my brain was either reading a book or watching something on television–and even as a child, I often read while I was watching television. (Which is why I read so much, even though that buzzing isn’t there anymore and hasn’t been for decades.)

As I get older and start revisiting my past (its traumas along with its joys) I begin to remember things, little clues and observations that stuck in my head as a lesson and remained there long after the actual inciting incident was long forgotten. I’ve always had a mild loathing for Truman Capote, for example, which really needs to be unpacked. Capote was everywhere when I was a child; there was endless talk shows littering the television schedules those days–Dick Cavett, Merv Griffin, Mike Douglas, John Davidson, and on and on and on–and Capote was always a popular guest on these shows. I wasn’t really sure what he did or who he was, but he was someone famous and he was on television a lot. I saw him in the atrocious film Murder by Death, and I know I knew/had heard that he was a homosexual, a gay; and I also knew I was a gay. It terrified me that I was destined to end up as another Capote–affected high-pitched speech and mannerisms, foppish clothing that just screamed gay at anyone looking; Capote made no bones about who or what he was and refused to hide anything…yet he gained a kind of celebrity and fame and success in that incredibly homophobic time period, and no one had a problem with putting him front and center on television during the day time.

But this isn’t about my own self-loathing as evidenced by my decades of feeling repulsed by Truman Capote; that I will save for when I finish watching Capote v. the Swans.

“Carissimo!” she cried. “You’re just what I’m looking for. A lunch date. The duchess stood me up.”

“Black or white?” I said.

“White,” she said, reversing my direction on the sidewalk.

White is Wallis Windsor, whereas the Black Duchess is what her friends called Perla Apfeldorf, the Brazilian wife of a notoriously racist South African diamond industrialist. As for the lady who knew the distinction, she was indeed a lady–Lady Ina Coolbirth, an American married to a British chemicals tycoon and a lot of woman in every way. Tall, taller than most men, Ina was a big breezy peppy broad, born and raised on a ranch in Montana.

“This is the second time she’s canceled,” Ina Coolbirth continued. “She says she has hives. Or the duke has hives. One or the other. Anyway, I’ve still got a table at Côte Basque. So, shall we? Because I do so need someone to talk to, really. And, thank God, Jonesy, it can be you.”

I do want to be clear that once I started reading Capote, he quickly became a writer whom I admired very much; I don’t think I’ve ever read anything he’s written that didn’t take my breath away with its style and sentence construction and poetry. He truly was a master stylist, and perhaps with a greater output he might have become one of the established masters of American literature, required reading for aspiring writers and students of American literature. In Cold Blood is a masterpiece I go back to again and again; I prefer his novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s to the film without question; and I was blown away by his debut novel, Other Voices Other Rooms, which was one of those books that made me think my childhood, and my being from Alabama, might be worth mining for my work.

I read “La Côte Basque 1965” years ago, and didn’t really remember it very much other than remembering I didn’t care for it very much. I was aware of the scandal that followed its publication and that all of Capote’s carefully cultivated rich society women friends felt betrayed by it and turned on him, which sent him into a decline from which he never recovered, before dying himself. I’ve always seen Capote as an example of wasted talents. Anyway, I read the story but not being familiar with his social set, I didn’t recognize any of the people gossiped about in the story or who the woman he was lunching with represented (Slim Keith, for the record), and so it kind of bored me; it was a short story about someone having lunch and gossiping about people the reader had no way of knowing who they were or anything about. I assumed this was because the story was an excerpt from the novel, and the novel itself would establish who all these women were and their relationships with each other. But I did know it was all thinly veiled gossip about his friends, and they never forgave him for it. (I also didn’t recognize “Ann Hopkins” in the story as Ann Woodward; I hadn’t known until the television series that he was involved in her story. I primarily knew about her from reading The Two Mrs. Grenvilles and articles in Vanity Fair, and I actually thought, when reading that book, that it was based on the Reynolds tobacco heir murder that Robert Wilder based his book Written on the Wind on; it wasn’t until later that I learned about the Woodward incident) so I thought, well, it was an entertaining if confusing read.

It was kind of like listening to two strangers talk in a Starbucks and gossip about people you don’t know; entertaining but nothing serious, not really a story of any kind, and I didn’t at the time see how it would all fit into a novel as a chapter in the first place. What purpose to the overall story did this nasty gossip play? Why was it necessary for Ina to share these stories at this particular lunch (and don’t get me started on White Duchess and Black Duchess)? Were these people she was talking about important to the book as a whole? It was hard for me to tell, and I put it away, thinking at the time probably a good thing he never finished the book.

Watching the show about fallout from the story’s publication, I decided to read the story again.

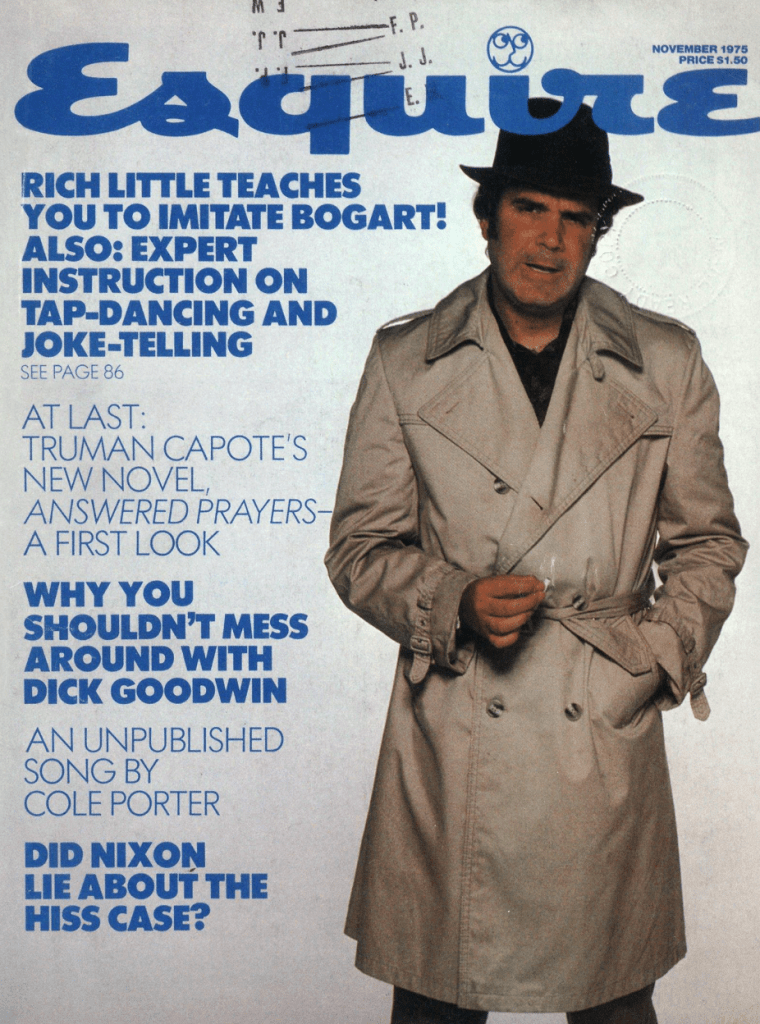

And I still question why Esquire chose to publish it, as well as why Capote thought this chapter was the one to send them. Capote was a genius, of course, and after In Cold Blood was one of the biggest names in American literature (he truly invented the true crime genre); of course they are going to publish whatever he sent them, no matter how bad it was. It wasn’t promoted as a story, after all, it was a novel excerpt.

What I’ve not been able to figure out from any of this is why he thought he could publish this without any fallout from his “swans.” I guess it went to the grave with Capote, who clearly didn’t–and I don’t think ever did–understand why they were so upset with him, which just astonishes me. (Someone once thought I based a character on her–I didn’t–and was very angry with me. I didn’t care, because I neither cared about the person nor her concerns, but I know how careful you have to be as a writer with these sorts of things.)

I wish I could say I liked it better on the reread. I did not. It’s still the same mess it was when I originally read over twenty years ago. It’s just a rich woman being bitchy to her gay friend she feels free to be bitchy about her friends with, and when you have no context (even knowing this time who the actual people were, and yes, he barely disguised them) about the women being discussed or anything about them…it’s just boring, gossip about people you don’t know and you don’t know enough to care about, so it’s just a bitchy little boring lunch. I don’t know what could come before that or after, as an author myself; had I been the fiction editor at Esquire I would have been pissed that was what he sent in, and I would have definitely taken a red pencil to it before I would have published it–and Esquire? Why did Esquire, a men’s lifestyle magazine, publish this when the right place would have been Vogue or Vanity Fair or even The New Yorker. None of it made sense then, none of it makes sense to me now; and if this is the best example we have of Answered Prayers, maybe it’s not such a bad thing that the manuscript–if it ever existed–disappeared.

Sorry, Truman, you were a great writer but this one was a swing-and-a-miss.