Ah, Alabama.

Despite everything that is wrong with Alabama culturally, societally, spiritually, and politically, I’m not ashamed of being from there (and never will be). I do shake my head with every new law passage or court ruling there that flies in the face of decency and the Constitution, because it is sad that the majority of people there are not only so lost spiritually and intellectually, but also defiantly cling to their backwardness. My part of the state, where my people are from, used to be very remote and rural; many native Alabamians, when I tell them where I’m from, are often confused, having never heard of it before. It isn’t on any interstate, rooming options are limited, and you really have to drive for about an hour from the nearest interstate to get there. It’s not quite as remote as it used to be; many of the roads that were dirt and/or gravel when I was a kid are paved now…but there are still plenty of unpaved roads up there in the hills and along the countryside. It’s very different there now, too–the country stores are all gone, and there’s definitely a lot more McMansions than there ever was when I was a kid. (Dad and I often marvel at the palatial homes we come across driving around the county, as Dad shows me places from his childhood and when he and Mom were first married.)

And it’s not cheap to buy property there, either, which was also a bit of a surprise.

Dark Tide was my first attempt to deal with my history and where I am from, but was cowardly in the end and wound up editing most of the backstory of my main character out. It didn’t really fit and made the book something different from what I was trying to do with the book, but as I edited it all out I also felt that I was being a bit cowardly. I knew I was going to have to deal with the troubled history (and present) of the county and state, so I wrote Bury Me in Shadows to not only try to get a better understanding of the area, but to deal with that troubled past. It wasn’t easy–I often found myself cutting things to a bare minimum in a stupid attempt to not give offense, and there were many times while writing it when I’d wince or skip a scene because I wasn’t sure how to word it properly without being preachy. I wanted to show through the story how refusing to face the past with a realistic and jaundiced eye can cause generational trauma and how that, in turn, perpetuates societal racism and homophobia in an endless cycle that strangles growth.

But writing that book also took me down a research wormhole that I’ve never really climbed back out of, and being there last weekend also reawakened some memories as well as creativity and potential future stories. (Dad and I found a really sad set of graves in the same cemetery as my maternal grandparents and uncle; parents and two small children –one was only four months–who’d died on the same day. We speculated as to how that happened, tornado or car accident or house fire, but a distant relative my father also knew explained that the father killed them all and then himself…which naturally started churning things in my brain again.)

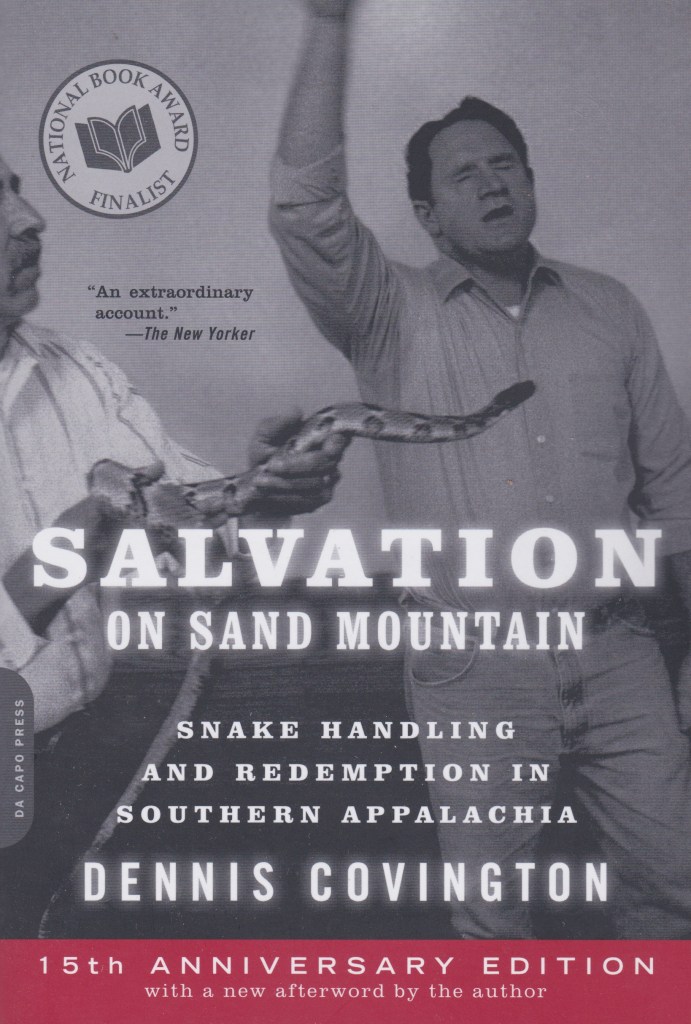

I also discovered, during the pandemic, a horrifying documentary called Alabama Snake, which focused on the snake handling churches of northeast Alabama and a minister who tried to kill his wife with snakes…and then discovered there was also a book about the culture from a reporter who’d covered the trial, and continued investigating and looking into the snake handling churches.

I finally read it last week.

The first time I went to a snake-handling service, nobody even took a snake out. This was in Scottsboro, Alabama, in March of 1992, at The Church of Jesus with Signs Following. I’d come to the church at the invitation of one of the members I’d met while covering the trial of their preacher, Rev. Glenn Summerford, who had been convicted and sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison for attempting to murder his wife with rattlesnakes.

The church was on a narrow blacktop called Woods Cove Road, not far from the Jackson County Hospital. I remember it was a cool evening. The sky was the color of apricots, and the moon had just risen, a thin, silver crescent. There weren’t any stars out yet.

After I crossed a set of railroad tracks past the hospital, I could see the lights of the church in the distance, but as I drew nearer I started to wonder if this was really a church at all. It was, in fact, a converted gas station and country store, with a fiberboard facade and a miniature steeple. The hand-painted sign spelled the preacher’s first name in three different ways: Glenn, Glen, and Glyn. A half dozen cars were parked out front, and even with the windows of my own car rolled up, I could feel the beat of the music.

It’s very difficult to think about Alabama without religion being involved in some way. Alabama is a very religious state, with churches everywhere–one of the things I always comment on whenever I am up there driving around with Dad is “there sure are a LOT of Churches of Christ up here”–you really can’t go anywhere without driving past at least two. Both of my grandmothers were devout (paternal family was Church of Christ; maternal Southern Baptist, although both my mom and uncle married into CoC and joined), but only the CoC was a fanatic with a Bible verse for everything and the uniquely American/Christian methodology of interpreting everything to justify her own behavior and conduct–which wasn’t actually very Christian (memorization doesn’t mean comprehension). I can remember driving around down there once with my grandmother–either in Alabama or the panhandle of Florida, where she wound up after retiring–and driving past a church (I won’t name it because she was wrong) and I said something and she sniffed in disgust. “They speak in tongues and take up serpents,” she replied. “Which is apostasy.”

Apostasy. What a marvelous word, and one that has always snaked its way through my brain, and comes up often whenever I talk about religion. But I digress; I will someday finish the essay in which I talk about my relationship with Jesus and my rejection of dogma.

I also liked the phrase “taking up serpents,” and always wondered why she said that instead of snake-handling.

I had originally thought, when I bought this book, that it was about the attempted murder by rattlesnake and subsequent trial, like the documentary I mentioned; rather it’s an exploration of this sect of Christianity by a curious reporter, and how being exposed to this style of worship made him rethink his own past, his relationship with his own faith, and about Alabama people in general. One of the reasons I enjoyed the book so damned much–even as I was repelled by its subject matter (snakes are the source of some of my worst nightmares; even harmless little garden snakes turn my stomach and engage my flight mechanism)–was because Covington has a very easy, natural and authentic authorial voice, and he really can put you into his mind as he witnesses and experiences this uniquely American brand of Christianity. It was also interesting as he got caught up in the entire experience, as he talked to the members of the various sects (there’s no national structure to the snake-handling churches, as there is with say the Southern Baptists or the Methodists), and watched them actually take up their serpents in the name of the Lord.

There’s also interesting information in the book about how these sects were created–or how they were descended from, surprisingly enough, the Methodists and how that evolved into these Appalachian sects, as well as where the people of the Appalachian regions came from, and that entire Southern mentality of fighting for their traditions and their “way of life” (it was also interesting that it’s a white phenomenon, at least as best I could tell in the book); of how they secluded themselves up in their mountains and hollows and were self-sufficient…but modern technology has forced them into a world that has left them behind.

I’ve always wanted to write about snake handlers…but as I mentioned before, snakes are the stuff of my worst nightmares, so yeah going to witness in person their rites is a big “no” from me, but I feel like I can maybe do that now, or at least make an attempt. I don’t know how much more research I’d need to do to fictionalize snake handlers, but some day it will happen.