I have always loved to read. I always escaped from the world into the pages of books, and quite often thought and/or believed that the world as it appeared in books was a much better place than the world I lived in. Being different from other kids, on top of all the other chemical imbalances and so forth going on in my head (hello anxiety!) left me constantly on edge; never knowing when the next unkindness or disruption to my life was going to happen. My parents worried often that I read too much instead of playing and doing little boy things–which never held much interest for me–but never knew that it was my life, and those societal little boy expectations, that I was trying so hard to withdraw from. I don’t know how old I was when I began realizing that the world was nothing like the books I read; and that interpreting and viewing the world from a perspective primarily gained from the reading of books for children–which were very much about establishing norms and behavioral expectations of kids–was a mistake. Even books for adults–which I started reading when I was about ten years old–didn’t really help me in dealing with the world.

But books were my solace and my job as a child, as a teenager, as a young adult, and even all the way through my thirties. I also drew comfort from rereading favorites over and over again; if I didn’t have the time to start something new I’d just take down an old favorite and reread it again. I recently realized I don’t do that anymore and haven’t in a while; on the rare occasions when I do reread something it’s a choice–“it’s been a while since I reread Rebecca, I should give it another whirl”–and just assumed it was because I have little time to read so I don’t reread anymore. That’s not the actual case; I could reread things instead of going down Youtube wormholes, but I don’t…because my life isn’t so horrible that I need that escape from it anymore and I don’t need the comfort from revisiting the familiar. This is progress, after all, and I am very happy about that realization.

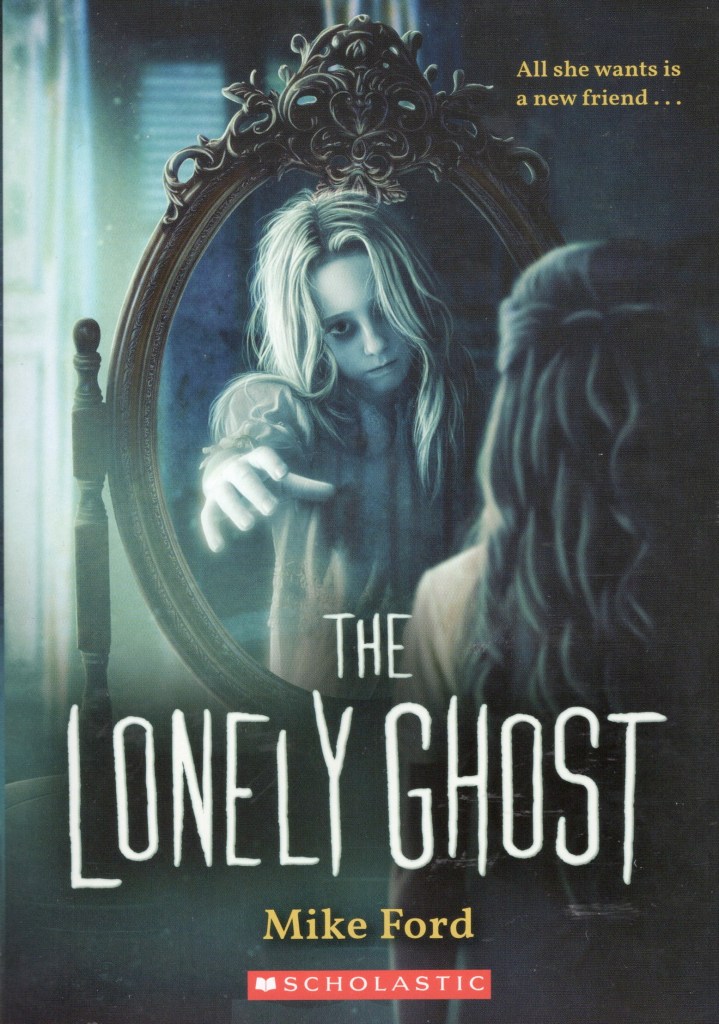

But I digress. I read a middle grade ghost story recently, and it was exactly the kind of book I used to look for at Scholastic Book Fairs and at the library.

“Ouch!”

Ava peered at her fingertip, where a bead of blood was forming. She stuck her finger in her mouth and glared at the rosebush she had been hacking away at with a pair of clippers. Her blood tasted coppery on her tongue and made her feel sick. She took her finger out and pressed her thumb against the spot where the thorn had pricked her. There was a little sliver of black visible beneath the pale pink skin.

“You need to get that out,” Cassie said. “You could get sporotrichosis.”

“Sporowhat?” Ava asked.

Her sister swept her long, dark hair out of her face and tucked it behind her ear. She, of course, was wearing gloves. “An infection caused by the Sporothrix schenskii,” she said. “It’s a fungus that grows on rose thorns. among other places,” she added when Ava stared at her with one eyebrow cocked. “Named after Benjamin Schenck, the medical student who first discovered it, in 1896.”

“Oh, right,” Ava said. “Benjamin Schenck.” She pointed at Cassie with the clippers. “Why do you know these things?”

“I was reading up about roses,” Cassie said. “Because of the garden and the Blackthorn roses. It just came up.”

“Most girls our age read about pop stars,” Ava teased.

I’ve debated about trying to write for middle-grade readers most of my life. While there were books I enjoyed when I was a kid, as I mentioned before, the stuff classified as “juvenile” in those days rarely depicted kids who were anything like kids I knew in real life; often-times the books always featured kids who never broke rules, never got annoyed or frustrated or angry; paragon children that the authors wished real world children would be more like. (The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew are perfect examples in their revised versions) I enjoyed the mysteries (and the historicals), but never could really relate much to the characters.

The Lonely Ghost isn’t one of those books, and as I mentioned earlier, had Mike Ford been writing these types of books when I was the right age for them, he would have been one of my favorite writers. Look how great that opening scene is–we meet the two sisters, get a sense of who they are and what their relationship is like predicated on how they speak to each other (sisters who love each other and are fond of each other but also are very different). This book follows the classic horror trope of an unsuspecting family moving into a spooky old house–either inherited, or purchased very cheaply–where they hope to make a new life for themselves, only to find the house isn’t what they expected. What we don’t learn about Ava and Cassie in that opening scene is they are fraternal twins–which is also incredibly important to the story. Ava’s more worldly and outgoing, a soccer star; while her sister is quieter, more studious, and into Drama Club, where Ava also ends up because they didn’t get her application for soccer in on time. But there’s something going on in the house that has to do with the previous owner–who also had a fraternal twin–and strange things start happening; and Cassie also starts acting strangely. Ava and her new friends have to get to the bottom of the haunting of Blackthorn House before it actually harms Cassie.

The book flows really well, and the girls–and their friendships–seem absolutely real. It’s been a minute since I’ve read something middle-grade, and aside from language and situations, the primary difference between it and young adult seems to be lower stakes in every way–no murders or sexual assaults or anything that might be too much for younger readers. It’s easy to get lost in the story because of a strong and compelling authorial voice, and the girls are all distinct enough within who they are and what they look like–which isn’t always the case–and it reads very quickly.

Mike Ford is the middle-grade authorial name for my friend Michael Thomas Ford, by the way, and yes, we’ve been friends for a long time but I also believe he is one of the best gay writers of our time and doesn’t nearly get the recognition or rewards that he deserves. I’m looking forward to reading more of these stories!