This is another one where I had the idea years before I actually sat down and wrote the damned book. I actually got the idea at my first ever Carnival; when I came as a tourist in 1995. We were at the Orpheus Parade on Monday night–I caught some beads thrown by Barbie Benton, if anyone remembers who she is–and I had noticed, at the parades since flying in late the preceding Friday for a long weekend, that the majority of the riders wore masks. I think I’d already known that, from books I’d read and movies and so forth, but seeing those plastic face-masks in person was a bit on the creepy side. I was already deeply in love with New Orleans–this was like the fifth or sixth trip I’d made there since my birthday the previous August–and that whole time I’d been thinking about how there had never been a New Orleans romantic suspense novel that I could recall; Phyllis A. Whitney wrote about New Orleans in Skye Cameron, but it was set in the 1880’s and I hadn’t much cared for the book (note to self: reread it!). I wanted something set in the present day, and as I caught more and more beads at the parade, it came to me: The Orpheus Mask.

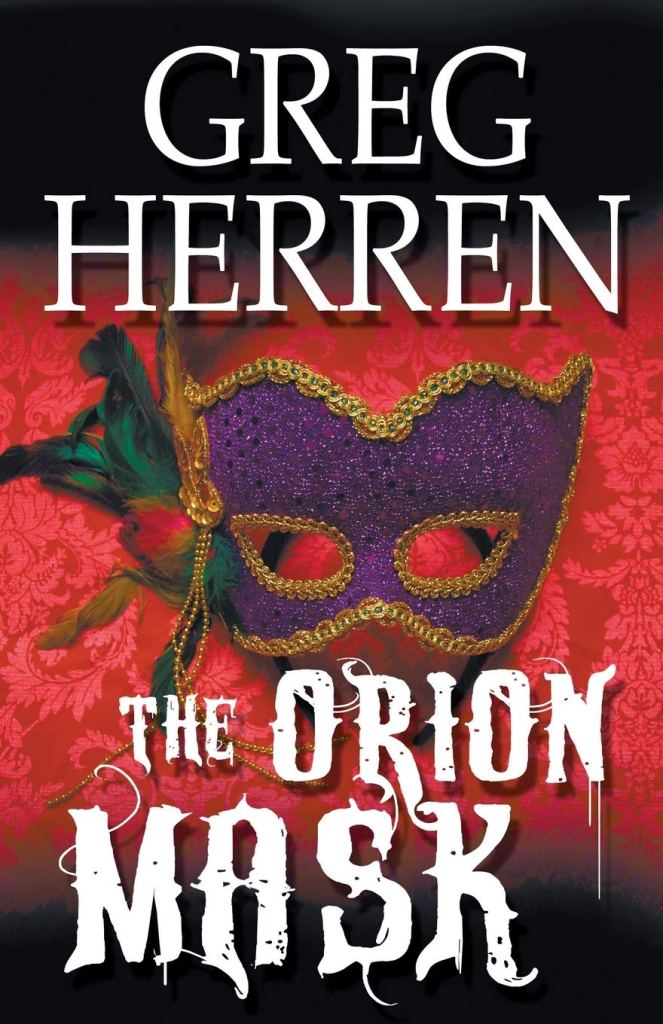

I somehow even managed to remember the idea after staying out dancing until late at night, scribbling it down in my journal the next day. I honestly don’t remember if I flew home on Fat Tuesday or Ash Wednesday, but I also don’t remember Fat Tuesday, so it makes more sense that I did fly back on Fat Tuesday. I was an airline employee, after all, and since I had to fly standby would I have waited to fly home until Ash Wednesday, when every flight would have been overbooked by about thirty, or would I have flown home on a lighter travel day, Fat Tuesday? I’ll have to find my journals (I’ve been looking for the old ones forever; I distinctly remember finding them a few years back but I don’t know where I put them; perhaps I can spend some time looking for them this weekend?) to check and be sure. But The Orpheus Mask idea was always in the back of my mind somewhere–even after I moved to New Orleans and realized I couldn’t use “Orpheus” in the title, but the krewe and its parade were far too new and modern to work in the story I was developing. Finally I decided to simply invent a krewe, the Krewe of Orion, and thus the book’s title became The Orion Mask.

I also always knew that The Orion Mask was going to be my attempt at writing a romantic suspense novel, using some of the classic tropes of the genre, particularly those used by one of my favorite writers, Phyllis A. Whitney. I grew up reading her juvenile mysteries (the first were The Mystery of the Hidden Hand and The Secret of the Tiger’s Eye) and then I moved on to her novels for adults, the first being Listen for the Whisperer, after which there was no turning back. I went and devoured her back list (I haven’t read all of the books for juveniles) and then she gradually became an author whose books I bought upon release in hardcover. The last I read was The Ebony Swan; the quality of the books had started to slip a bit as we both got older plus the world and society had changed; even I had noted earlier that her characters were often–I wouldn’t go so far as to say doormats, but they didn’t seem to stand up for themselves much, and often the “nice” heroine was put in competition and contrast to an “evil” villainess; a scheming woman who didn’t mind lying and scheming to get what they want–which also included tormenting the “nice heroine”. (There were any number of times I thought read her for filth or whatever the saying for that at the time was.) My main character wasn’t going to be a pushover or weak; but I also wasn’t going to make him an asshole, either.

Taking this trip was probably a mistake I would regret.

I finished my cup of coffee and glanced over at my shiny black suitcases. They were new, bought specifically for this trip. My old bags were ratty and worn and wouldn’t have made the kind of impression I wanted to make. My cat was asleep on top of the bigger bag, his body stretched and contorted in a way that couldn’t possibly be comfortable. I’d put the bags down just inside my front door. I’d closed and locked them securely. I’d made out name tags and attached them to the handles. I’d taken pictures of them with my phone in case they were lost or misdirected by the airline. My flight wasn’t for another three and a half hours, and even in heavy traffic it wouldn’t take more than fifteen minutes to get to the airport. I had plenty of time; as always, I’d gotten up earlier than I needed to, and finished getting ready with far too much time left to kill before leaving for the airport. I checked once again to make sure I had my airline employee ID badge, my driver’s license, my laptop, and the appropriate power cords in my carry-on bag. I was flying standby, of course, but I’d checked the flight before leaving work the previous night and there were at least thirty seats open with a no-show factor of fifteen The only way I wouldn’t get on Transco flight 1537 nonstop from Bay City to New Orleans was if another flight to New Orleans canceled or this one was canceled for mechanical problems. But should that happen, I had my cousin’s cell phone number already loaded into my phone so I could give her a call and let her know what was going on.

I got up and poured what was left in the pot into my mug, making sure I turned the coffeemaker off.

The occupational hazard of flying standby was that your plans were never carved in stone and were subject to change at any moment.

They’d offered to buy me an actual ticker, of course, but I’d said no.

I wasn’t really ready to take any money from the family I didn’t know just yet.

I sipped my coffee. Has it really only been two months? I thought again.

I’d known they’d existed, of course, since that day I accidentally found my birth certificate when rooting around in my father’s desk drawer.

Phyllis A. Whitney’s books almost always involved two things: a murder in the past that cast shadows on the present, and someone going to meet a family they’ve been estranged from–usually not through any fault of their own–since their childhood. Another popular trope was that the murder involved one of the main character’s parents; in this case, I made it his mother. I named him Heath Brandon (after a co-worker), and the mystery from the past was his mother’s death. When Heath was a very small child, his mother was murdered by her lover, who then committed suicide. Heath’s father–never a fan of her family, the Legendres–took his son and left, cutting off all communications and never telling Heath anything about his mother. He always knew his father’s second wife wasn’t his mother, but all he knew about his mom was she died when he was young and talking about her upset his father, so he never brought her up and never even knew her name.

His father is now dead and Heath is working at the Bay City Airport for Transco Airlines (my go-to whenever I need an airline), when one night he notices a very attractive bald man in a tight T-shirt and jeans watching him work at the ticket counter. When the man appears the next night, Heath wonders if he should report him to security–but the man approaches him, invites him out for a drink and promises to tell him about his mother’s family. Heath in intrigued–he found out about how his mother died after finding his birth certificate and doing some on-line searches. But the man–Jerry Channing, who has also popped up in the Scotty series–is actually a true crime writer who doesn’t necessarily believe the story of how Heath’s mom and lover died, and is looking into it with an eye to writing a book. Jerry puts Heath in touch with the family, and now…he is going to meet them.

The Legendre plantation, Chambord, has been in the family for centuries. At one point, it became known for glass-making; I tied this somehow into Venetian glass, particularly the famous Murano style, and while the glass-making has long since fallen by the wayside, Chambord houses a Chambord glass museum on the property as well as a high-end restaurant–and also does the de rigeur plantation type tours. Once Heath arrives, any number of mysteries present themselves to him: why is his first cousin bear him such animosity? Why does is aunt? Why is everyone so afraid of his grandmother? And he begins to feel an attraction to his cousin’s handsome, sexy cousin–who runs the restaurant with her. Their marriage doesn’t seem happy–his cousin is kind of a bitch, as is his aunt Olivia–and he gets signals from the married restauranteur. Could it be?

And then, is it his imagination or has someone tried to kill him?

He also inherits his mother’s house in the lower Garden District of New Orleans (a house that is real and I’ve been in love with for decades), and when he goes to stay there for a night or two, he discovers a clue to the dark secrets that hang over Chambord–and what really happened in the boathouse when his mother and her lover died.

One of the things I realized while writing The Orion Mask how freeing it was for me to write a Gothic with a gay main character; Whitney and her colleagues were constrained by the rules of their genre and what their readers expected these books to be. I didn’t have either those fears or constraints; and whenever I would think oh I can’t do that Whitney would have never–then I would stop and think, you aren’t Whitney and you aren’t writing in her time period, and besides, your main character is a gay man not a young woman; of course you can do that even if its against the rules!

That realization also made me admire the talents and skills of Whitney and her contemporaries, and what they were able to accomplish within the boundaries of their genre, even more than I had previously. I will most likely write more of these style books in the future; it was a lot of fun writing this and playing with the conventions of romantic suspense.

Chambord was sort of based on Houmas House–I think I even reference that “Chambord” was made famous by a film with two aging stars that was filmed there (obviously, Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte); I also referred to Belle Riviére in Murder in the Arts District that same way.

The joys of a Greg multiverse!