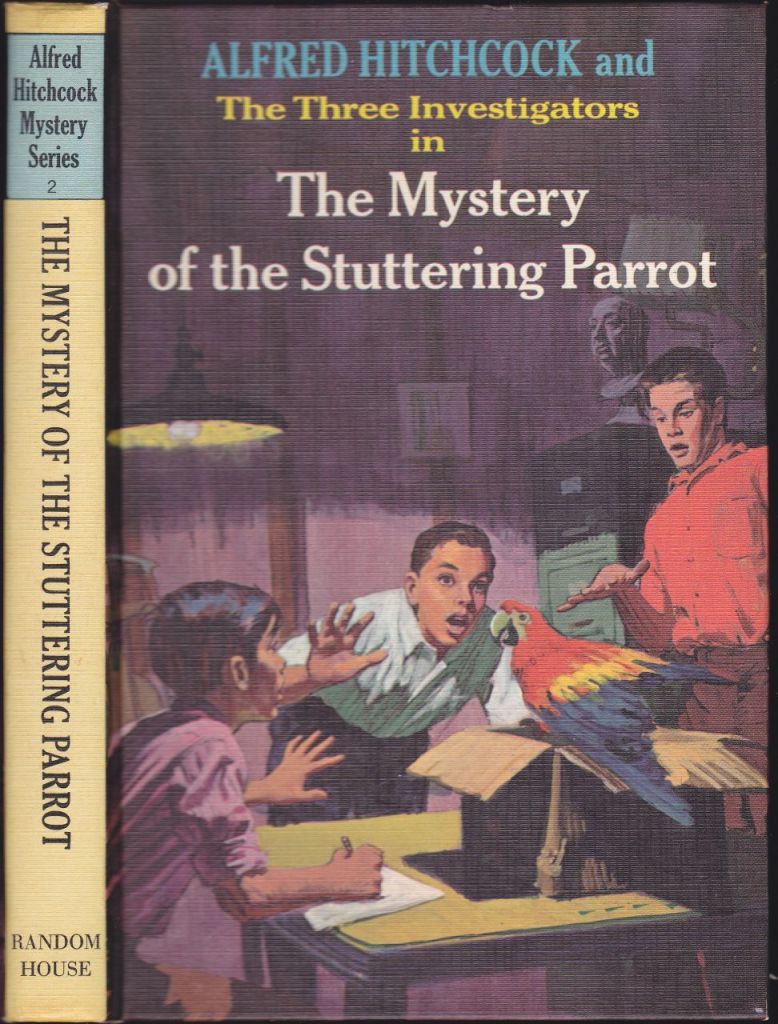

I loved the Three Investigators.

When I was writing about rereading “The Birds” the other day, it brought Alfred Hitchcock to mind again. I have been revisiting the old Alfred Hitchcock Presents anthologies lately, and slowly (finally) realizing what an enormous influence on my writing Mr. Hitchcock was. Obviously, there’s the films, and the television series, of course, but even more so in books–books he had little to do with other than licensing his name–because hands down, no questions asked, my favorite juvenile series was The Three Investigators. I loved those books, and still do. The Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, the other series–they don’t really hold up well for me now, but I can still enjoy the The Three Investigators as much today as when I first read them. The books are incredibly well written, and the three boys themselves are very distinct from each other yet not one-dimensional, and that holds true for all the members of their supporting cast–Uncle Titus, Aunt Mathilda, Hans and Konrad, Hitchcock himself, Worthington the chauffeur–as well as the primary settings, the Jones Salvage Yard and Headquarters, a wrecked mobile home hidden in plain sight, beneath and behind piles of junk, with secret tunnels leading to it.

What I liked the most, though, was that the plots of the mysteries themselves were very intricately plotted, and the criminals were actually pretty smart, so it took a lot of good detective work, thinking, and intelligence to outwit them. Many of the books were treasure hunts, which of course I love love love, and often required the solving of a puzzle, which I also loved. The three boys who formed the investigation were Jupiter Jones, Pete Crenshaw, and Bob Andrews. Jupiter (First Investigator)had been a child star on a Little Rascals type television show as “Baby Fatso”, which he doesn’t like being reminded of, or being called fat (this was actually one of the few kids’ series that dealt with fatphobia and flat out said making fun of people for being overweight was cruel; think about how much Chet Morton gets teased for being fat in The Hardy Boys and the same with Bess Marvin in Nancy Drew); he is also the brains of the outfit. He has a quick deductive mind, pays attention to details, and has read a lot so he’s got a lot of arcane knowledge in his mind that comes in handy quite often. Pete (Second Investigator) is strong and athletic and not nearly as bright as Jupiter. Pete also gets scared easily, but an ongoing theme in the books is how Pete always overcomes his fears to come to the aid of his friends. Bob Andrews is Records and Research; he works at the local library so can do research for them, and he also is the one who writes up all their cases to present to Mr. Hitchcock, to see if it’s worthy of his introduction. When the series begins, he has a brace on one leg from a bad fall down a nearby mountain–so he doesn’t get to get involved in any legwork or in-person investigations for several volumes until the brace comes off.

And of course I loved learning from Jupiter’s vast stores of knowledge.

“Help!” The voice that called out was strangely shrill and muffled. “Help! Help!”

Each time a cry from within the mouldering old house pierced the silence, a new chill crawled down Pete Crenshaw’s spine. Then the cries for help ended in a strange, dying gurgle and that was even worse.

The tall, brown-haired boy knelt behind the thick trunk of a barrel palm and peered up the winding gravel path at the house. He and his partner, Jupiter Jones, had been approaching it when the first cry had sent them diving into the shrubbery for cover.

Across the path, Jupiter, stocky and sturdily built, crouched behind a bush, also peering toward the house. They waited for further sounds. But now the old Spanish-style house, set back in the neglected garden that had grown up like a small jungle, was silent.

“Jupe!” Pete whispered. “Was that a man or a woman?”

Jupiter shook his head. “I don’t know,” he whispered back. “Maybe it was neither.“

Jupe and Pete are on their way to call on a prospective new client, referred to them by none other than Alfred Hitchcock himself. Professor Fentriss had bought a parrot from a peddler, primarily because he stuttered and was named Billy Shakespeare (Fentriss is an English professor). The parrot says “to-to-to be or not to-to-to be, that is the question.” But this is in and of itself mysterious, as Jupe points out, because parrots don’t stutter; they have to be taught to stutter. Why would anyone teach a parrot to stutter? But the stuttering parrot is just the start of a bizarre and unusual case, with twists and turns and surprises everywhere the boys turn. Their detecting soon leads them to the revelation that there were six parrots and a mynah bird the peddler was selling, and they were all taught specifically to say one phrase. The phrases are clues to a treasure trail, and the prize is a magnificent and incredibly valuable painting by a master.

This book is an excellent example of precisely why I loved this series so much. The pacing is always excellent, the characterizations are three-dimensional, the mystery is intricate and puzzling and hard to figure out, and the conclusion of the book, where the boys have to beat several bad guys to actually find the painting, which takes place in a spooky abandoned cemetery on a foggy night, is some of the best atmospheric writing I’ve ever encountered. You really feel like you’re lost in the fog with bad guys you can’t see out there somewhere.

I’ve never understood why these books never achieved the popularity of the Hardy Boys and other series like them. They were better written, better stories, and just over all vastly superior to the Hardy Boys in every way. The first book in the series, The Secret of Terror Castle, remains one of my favorite kids’ books to this day (several books from this series make that same list). The problem with the series was time, really. Alfred Hitchcock eventually died, and they had to get someone else to fill in for him. Eventually, recognizing that Hitchcock’s name alone dated the books, they removed the references. The books themselves were never updated, which is also a shame because it dates the books but at the same time gives them a kind of nostalgic charm, as well. The Secret of Terror Castle was about the home of a silent film star whose career was ended by talkies, who turns out to be still alive. That was a stretch for me even when I first read it in the early 1970’s, let alone today. Whenever I think about writing my own kids’ series, I always think of it in terms of being Hardy Boys-like, but really what I would want to do is emulate the Three Investigators, whose books were well-written and a lot of fun to read.

Be sure I will talk about them again another time.