John Copenhaver, one of queer crime’s latest (and brightest) stars recently (you should read his books, frankly; I am looking forward to his latest, Hall of Mirrors) wrote a brilliant essay on the concept of writing complex queer characters, and the artistic need to push beyond ‘gay is good’ messaging and not worrying about the question of role models which you can read by clicking here. I highly recommend it–it’s well thought, reasoned, and stylishly written, and the kind of thing I wish I could write.

But reading this essay made me think about my own work, the pressures I’ve had–either real or imagined–about representation and addressing social issues through the framework of queer people and characters, and made me think about the work I do from not only a creative view (which is how i always view my work) but from a cultural, political, and societal perspective. That’s not something I’ve ever really consciously done (“oh, let’s make this political“) but one thing I’ve never done is worry about how straight people might react to my work…primarily because it isn’t really for them that I write my books in the first place. If my work offends straight people that isn’t my problem, nor is their whining about how queer people see and perceive them…and it’s not like there aren’t millions of books designed as comfort reads for cishet white people. I’ve also never understood taking offense at a book. I’ve read plenty of books whose point of view I’ve neither understood nor care to; and I tend to not read anything that I think is going to either offend me or be antithetical to everything I read–I tend to avoid Westerns, international spy thrillers, and war novels, and mostly for the same reason I tend to avoid most cishet white male authors. Your work isn’t written for me, and I can’t imagine westerns to be not problematic1–likewise, I’m not interested in reading about toxic male he-men that are racist rah-rah-rah books to make white men feel better about themselves (you know who you are) and so I avoid covers that pretty much spell out to me what the contents are going to be–women who exist only to be beautiful sex toys, any gay characters are offensive stereotypes and usually die, and so on and so forth; I love my country in spite of its flaws, and that love is strong enough to bear critiques on our nation and the people who run it, so I don’t need to read fiction designed to make me thump my chest and scream AMERICA LOVE IT OR LEAVE IT at anyone who dares critique the country and its domestic and foreign policies.

If cishet white people enjoy my work, fine. If they don’t, well, as I said it isn’t intended for them in the first place.

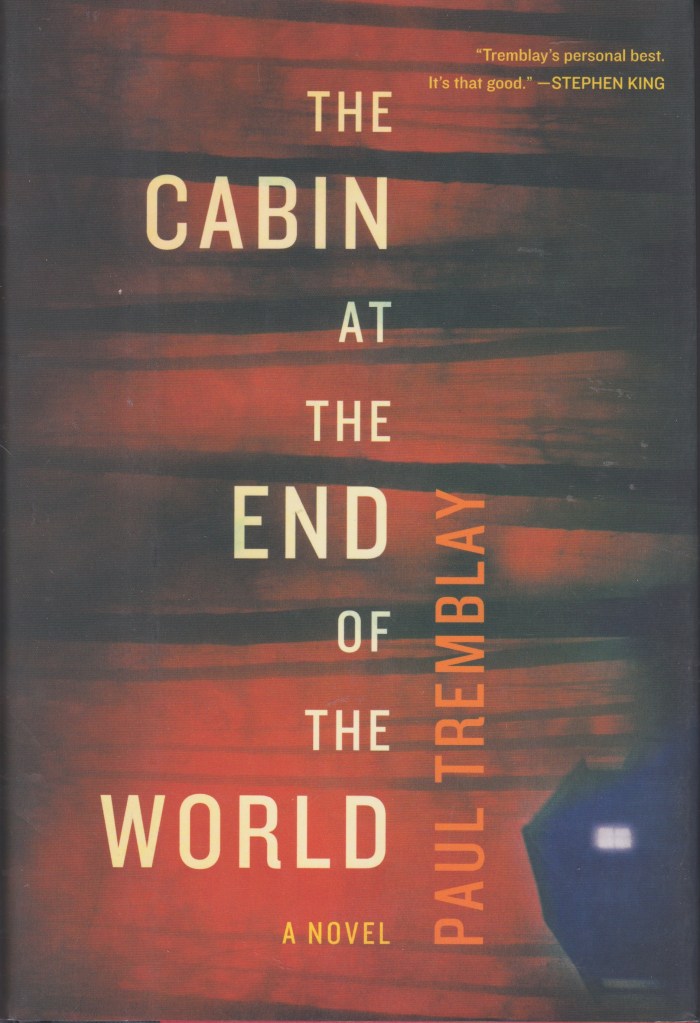

When I first dreamed of being a writer, it never occurred to me to write about gay characters or themes. I was a child, for one, and for another that child was terrified that anyone might figure out that I wasn’t one of the “normies”, and what I actually was inside was something they’d all view with contempt. When I was a kid I wanted to write a kids’ series, like Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys, and even came up with multiple different ones that I wanted to write, and came up with a rather lengthy list of titles for the books (which I still have, because I’d still like to try this at some point before I die), and gradually moved on to wanting to write other styles of books as I got older and began reading more. My addictions to soaps, both daytime and nighttime, during the late 1970s thru the early 1990’s, had me looking at writing more about towns and large casts of characters, and I always wrote a murder mystery into my ideas for these Peyton Place type novels I wanted to write; I also wanted to write Gothic suspense novels, and Stephen King had me also wanted to write mainstream horror novels…and later on, I moved into wanting to write horror/suspense/crime novels for young people.

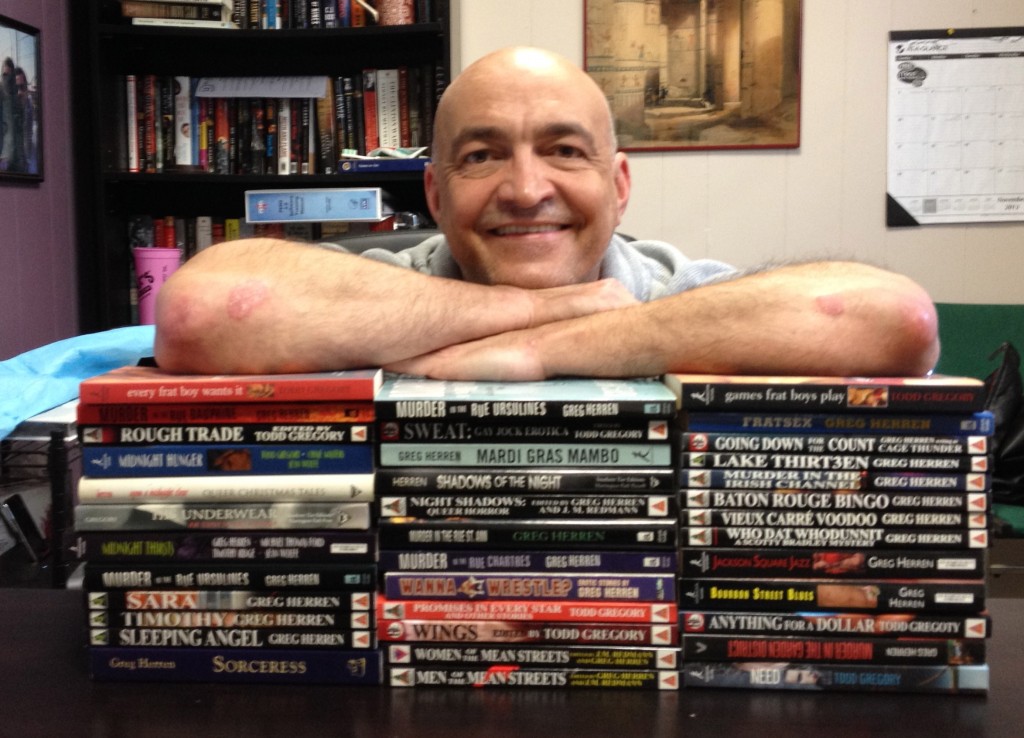

It wasn’t until I met Paul, and I found gay bookstores, that I realized I could write gay stories and themes and characters, and I decided I wanted to write gay crime novels, set in New Orleans, and so that’s what I set out to do, starting a novel called The Body in the Bayou, which I had already thought up as a series about a straight Houston private eye–so I made the main character gay and moved it to New Orleans. I threw out the first ten chapters within two weeks of moving here, and started over again.

And then I found myself in the conundrum John talks about in his essay so brilliantly; is it okay to have queer characters be the bad guy? Do we have to write all of our stories and novels from a thematic viewpoint that ‘gay is good’? Do we as creators have a responsibility to the community to only present queer people as heroic, or can they be flawed or even bad?

I’ve talked about this before–how the idea for the case in Murder in the Rue Dauphine came to me, and I also worried about how the book would be received because I was explicitly creating a case and a world where not all queer people were good people. It was inspired by a gay man who came to New Orleans, got involved in the non-profit world here, threw a bunch of money around, and then disappeared overnight as his house of cards was about to collapse, stealing a shit ton of money and owing everyone a lot of money. That was when I realized how we always are welcoming to other queer people and we can sometimes overlook red flags and warning signs because you’re working with another queer person. We tend to give other queer people the benefit of the doubt and more chances than we would a straight person…and I wanted to explore that in fiction. Shining heroes without feet of clay also aren’t fun or interesting to write about, either.

Gay isn’t always good.

And we aren’t doing our readers any services by creating “perfect” characters, either. Neither Chanse nor Scotty is perfect (although Scotty’s definitely an idealized person, I have to admit, but he does have flaws and blind spots) and the main characters in my stand alones are often messy, sloppy people who need to get out of their own way sometimes. Those are the kinds of characters I like to read about–because they are human.

I also find gay criminality enjoyable to read. James Robert Baker’s books were like being slapped in the face; full of gay anger and revenge and bitterness about the homophobic world in which we all exist–but Baker’s messy characters are active; they want revenge on the world and by God they are going to get it. The Ripley books by Patricia Highsmith are magnificent. Christopher Bollen’s A Beautiful Crime was terrific with its messy gay characters perpetrating a fraud.

I think we relate to and enjoy messy criminal queers because they are so relatable to us. There’s no worse feeling than powerlessness, the inability to control your own destiny and life, and always wondering …is it because I’m gay? I’ve gotten angry about this any number of times during my life, and I have always wondered somewhat would this happen to a straight man? and the answer is always no.

But do read John’s article. It’s very well done and thought provoking, and I’m going to let it simmer in my head for a while longer.

- Westerns would be a good discussion for another time, actually.

↩︎