I know very little about the culture, history, values, and faith of the native American population of this continent. Most of what I do know isn’t reliable; being gleaned from books and histories and television shows and movies and other media, most of which were steeped in racism and white supremacy, and cannot really be depended upon for any kind of accuracy whatsoever.

If anything, it should be looked at with a highly jaundiced and very critical eye.

I’ve been trying to educate myself more about the indigenous natives of Alabama, for example; as I delve more deeply into writing about my fictional Corinth County, I need to learn more about the area and the natives who originally lived there–and what they believed and their spirituality. I do not want to write–or even imagine– anything rooted in white supremacy and racism. I never played “cowboys and Indians” when I was a child–I was never into little boy things, ever–and was never terribly interested in Westerns, but was aware that white people wore thick make-up to play Native-Americans on film and television…which even as a child made me wonder why they didn’t just find Native-Americans who wanted to be in show business (because I found it incredibly hard to believe there weren’t any). I always assumed Cher was at least part Native because of “Half-Breed,” so you can imagine my shock and surprised to find out she’s actually of Armenian descent. The Village People had a non-native in native garb as part of their nod to gay masculine archetypes (probably this came from the book and movie Song of the Loon, plus decades of Hollywood’s sexualization of the loin-clothed Native warrior).

And as you get older, and do more reading and studying on the subject, you begin to see things that were plainly obvious all along, but somehow you never really connected the dots.

The first time I ever read anything that treated the native population with dignity, respect and understanding was James Michener’s Centennial*, which remains my favorite of his works and one of my favorite books of all time. The hit movie Billy Jack, which came out while I was in junior high school, was also about mistreatment of modern-day Natives by bigoted white people and their government, but I think the social message of the movie got lost in white tween boys’ fascination with Billy Jack’s fighting skills, because that was all they talked about. I don’t think I ever heard anyone ever say “It’s terrible how we treat the natives.” The late 1960s and 1970s began to see a change in how we see the native population, as well as the history of the European conquest of the continent–not everyone, of course, but at least with those who were trying to be better about racism and racial issues and the long history of oppression of the native populations.

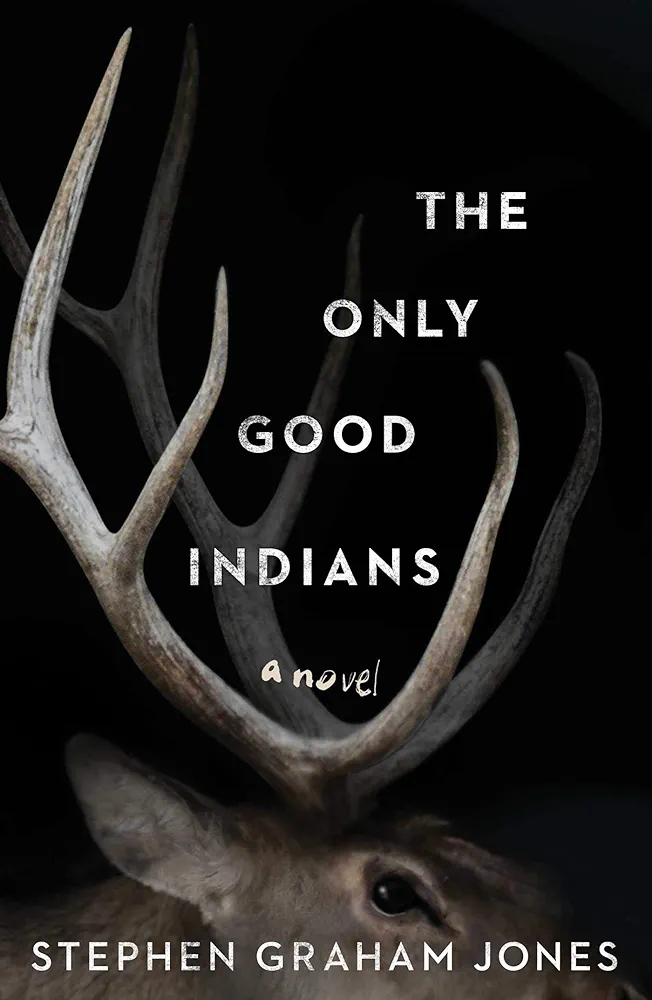

I had heard a lot of great things about Stephen Graham Jones, a native American horror writer who has taken the genre by storm. I’ve been wanting to read him for quite some time, and so I decided to listen to The Only Good Indians on my drive to Panama City Beach and back this past weekend.

And it did not disappoint.

The headline for Richard Boss Rivs would be INDIAN MAN KILLED IN DISPUTE OUTSIDE BAR.

That’s one way to say it.

Ricky had hired on with a drilling crew over in North Dakota. Because he was the only Indian, he was Chief. Because he was new and probably temporary, he was always the one being sent down to guide the chain. Each time he came back with all his fingers he would flash thumbs-up all around the platform to show how he was lucky, how none of this was ever going to touch him.

Ricky Boss Ribs.

He’d split from the reservation all at once, when his little brother Cheeto had overdosed in someone’s living room, the television, Ricky was told, tuned to that camera thay just looks down on the IGA parking lot all the time. That was the part Ricky couldn’t keep cycling through his head: that’s the channel only the serious-old of the elders watched. It was just a running reminder of how shit the reservation was, how boring, how nothing. And his little brother didn’t even watch normal television much, couldn’t sit still for it, would have been reading comic books if anything.

First of all, I want to address what a terrific writer Jones is–although this is hardly ground-breaking news. For me, the strongest part of the story was the authorial voice and the tone set by it. I can’t say whether something like this–like anything written by people outside of my own experience–is authentic or not, but it was completely believable. I truly got a sense of what it is like to be a Native-American living in North America in the present day; the mind-numbing poverty and dealing with the incessant racism from white people. His characters were three-dimensional and fully realized; the dialogue sounded right, the rhythm of the words he used to create a melody of syllables and sounds sang from the page. I felt like I was there in every scene, in the room with the characters and bearing mute witness to what they were experiencing, and what they were going through and experiencing, with the fully-realized life experiences coming into play with every word they said and every action, every thought, every movement. The deceptive simplicity of the prose was powerful and resonated; it sounded like poetry coming through my speakers.

I also found myself really interested in basketball–which is very unusual.

I also realized, as I was listening, spellbound behind the wheel of my car, that there was also commonality of human experience here; the poverty, the worries about money and the future and the bleakness of the helpless acceptance of despair–this is definitely a horror novel, but it’s also a stinging indictment of poverty and societal inaction in the face of it; their resigned acceptance of their fate mirrors the more callous resignation most people feel when thinking about poverty in these United States–“nothing I can do about it.”

While telling a strong story that is almost impossible to step away from, Jones also educates us cleverly with a sentence here and there–I’d never thought about where the term buck naked came from, and there are so many of these sprinkled throughout the book; terms and phrases that white people use without a second thought but come from a long history of racism and prejudice; the title itself is taken from the horrific saying “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” I myself am always careful not to refer to the native population by the colonizing name assigned to them by the lost Spaniards looking for spices; it was jarring hearing it over and over again, and made me a bit uncomfortable–but I suspect that was the entire point. (I think the worst was when the junior high school basketball prodigy Denora was thinking about playing a game against white schools, and the horrible signs and things their students yelled at her and her teammates–the one that was particularly offensive was Massacre the Indians!, which reminded of the trash Chicago Bears fans holding up signs when playing the Saints in the NFC title game after the 2006 season: “FINISH WHAT KATRINA STARTED!”, which turned me from someone with a nostalgic affection for the NFL team in the city where I spent most of my childhood into someone who wants them to lose every fucking game they play.

Massacre the Indians.

There’s no doubt in my mind reservation kids have to deal with this kind of bullshit all the time, and its embarrassing and infuriating at the same time. The cruelty is always the point.

But I digress.

I really enjoyed this book. I felt like reading it somehow helped me reach a better understanding of a situation I was already aware of, while being incredibly entertaining at the same time. I cannot state that enough: what a great experience this book was from beginning to end. The tension and suspense were ratcheted up with every chapter and sentence; the monster was terrifying and horrifyingly relentless, and the characters were all strongly rendered in both their strengths and their flaws.

When I finished the book, I couldn’t help but wonder if this book, and others by Jones, were being pulled from library shelves because reading them might make white people feel bad. The book made me remember again why controlling access to what anyone can read is about control more than anything; we can’t let people read diverse points of view or see opposing opinion is the underlying message of the banners, and quite frankly, grow a fucking pair already! Seriously, who is calling who a snowflake?

Read this book! You can thank me later. And now I want to read more of Jones’ work.

*Centennial may not have been historically accurate in its depiction of the Arapahoe tribe, but I feel that it showed how the US government broke promise after promise to them, and the depiction of their systemic extermination was not done in a “manifest destiny” way. The ugliness of the US and its racism was right there on full display.