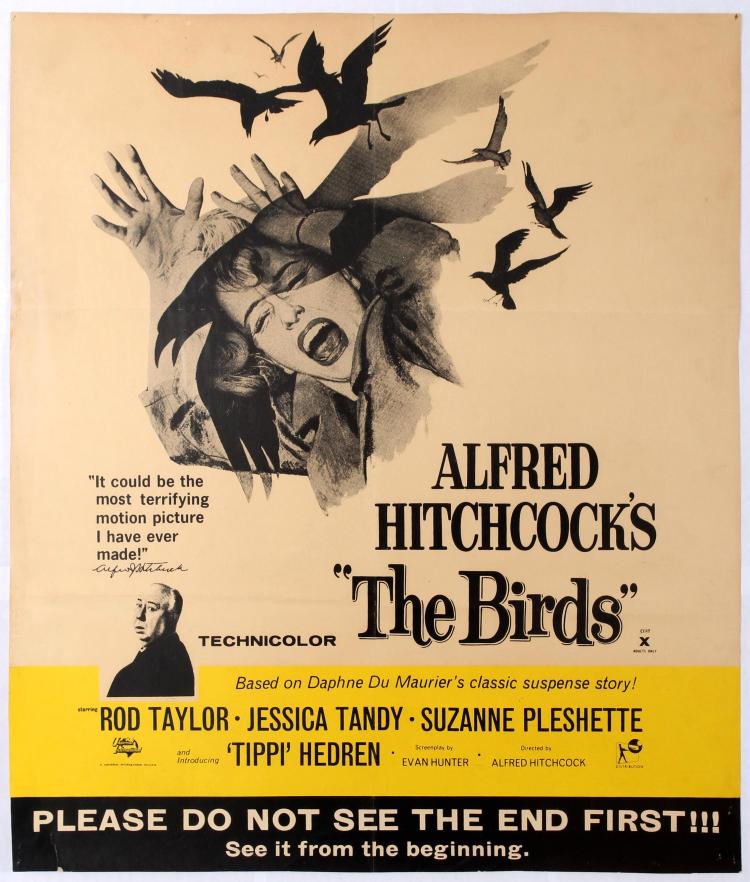

One of the first Alfred Hitchcock movies I ever saw was The Birds. We watched it on our big black-and-white television, and it was absolutely terrifying. What made it even more terrifying was that we as viewers–along with the characters in the film–had no idea what had turned the birds into vicious flocks of attacking predators. The movie was absolutely terrifying to a very young Gregalicious, who ever after always gave whatever birds he saw a wary look. That innocuous scene where the birds start gathering on the jungle gym? First a few that you notice, then you look again and there’s more… you look back another time and there are even more….more and more with every look until you have a sick feeling and think maybe I better get out of here–yes, I related absolutely to that scene in the movie and whenever I see a flock of birds gathered anywhere I have a bit of an uneasy feeling. You never really think about how vicious and terrifying birds–descended from the dinosaurs, after all–can be. Sure, we all know about the birds of prey, with their sharp claws and razor-like beaks; but sparrows? Blackbirds? Crows? How do you defend yourself if a flock comes for you? God, even now, just thinking about it gives me goosebumps.

I recently rewatched the movie (during the Rewatch Project during the pandemic) and it’s not as good a film as I remembered, but it’s still terrifying. I was curious to see how I would react to the movie, because in the intervening years I had read the short story it was based on, and the story is much, much better than the movie.

The fact it was written by Daphne du Maurier didn’t hurt.

On December the third the wind changed overnight and it was winter. Until then the autumn had been mellow, soft. The earth was rich where the plough turned it.

Nat Hocken, because of a wartime disability, had a pension and did not work full time at the farm. He worked three days a week, and they gave him the lighter jobs. Although he was married, with children, his was a solitary disposition; he liked best to work alone, too.

It pleased him when he was given a bank to build up, or a gate to mend, at the far end of the peninsular, where the sea surrounded the farmland on either side. Then, at midday, he would pause and eat the meat pie his wife had baked for him and, sitting on the cliff’s edge, watch the birds.

In autumn great flocks of them came to the peninsula, restless, uneasy, spending afternoons in motion; now wheeling, circling in the sky; now settling to feed on the rich, just turned soil; but even when they fed, it was as though they did so without hunger, without desire.

Restlessness drove them to the skies again. Crying, whistling, caslling, they skimmed the placid sea and left the shore.

Make haste, make speed, hurry and begone; yet where, and to what purpose? The restless urge of autumn, unsatisfying, sad, had put a spell on them, and they must spill themselves of motion before winter came.

I love Daphne du Maurier.

The story was originally published in her collection The Apple Tree and Other Stories; when the film was released in 1963 it was rereleased as The Birds and Other Stories. (One of the problems with trying to read all of du Maurier’s short stories is because her collections inevitably have at least half the stories that have appeared in other collections; so you can wind up buying a collection for the two or three stories in it you’ve not read; for example, my first du Maurier collection was Echoes from the Macabre, which included “The Apple Tree” (title story of another collection) AND “Don’t Look Now” (also the title story of another collection) AND “Not After Midnight” (which, as you probably already guessed, is the title story of another collection). I have yet to find a definitive list of du Maurier’s short stories anywhere, and it certainly is long past time that all of her stories are collected into a single collection (are you listening to me, du Maurier estate?).

The reason I love the story so much is because it really is a master class in tension and suspense. It’s also a much more intimate, small story than the film. Nat is a simple worker, loves his wife and kids, and wakes up one morning to winter and bizarre behavior from the birds. The way du Maurier describes the sight of the seagulls all gathered out on the sea, rising the waves in silence, is creepier than any shot of Suzanne Pleshette sprawled out on the walk with her eyes pecked out. The radio–there only method of communication and getting news from the rest of the world–is reporting on the strange behavior of the birds, and that they are attacking people. Most of the action–the truly terrifying action–takes place inside Nat’s cottage while they are under siege; the attacks have something to do with the tides. During the lulls he boards up the windows and tries to lay in supplies, as he slowly begins to realize that the birds are winning. They wait out the attack one night and in the morning turn on the radio…only to get static. It soon begins to feel like they are, or may be, the only humans left alive. And Nat also realized that it’s just the smaller birds–sparrows, wrens, seagulls–and worries about what will happen when the birds of prey join in….and of course, they do…the story closes with the hawks attacking the front door while Nat resignedly waits for them to get through.

If I were teaching a suspense writing class, I would definitely teach this story. It’s simply brilliant.