Being from, not only the South but also from Alabama, I am very particular about Southern fiction, and fiction set in Alabama (there is more of it than you might think; there is certainly much more of it than To Kill a Mockingbird). Robert McCammon has written some exceptional Southern horror fiction set in Alabama; I absolutely loved Boy’s Life, while I have yet to read Gone South (which is in the TBR pile). He actually set a book in the part of Alabama I am from; it was a good book, but it bore no more actual resemblance to that county than anything other book set in the rural South; it was as though he simply put up a map of Alabama and stuck in a pin in it, said “okay this is where it will be set” and worked from there. But it was a good book that I enjoyed; it had some interesting things to say about religion–particularly the rural Southern version of it. I myself want to write about Alabama more; I feel–I don’t know–connected somehow when I write about Alabama in a greater way than I do when I am writing about New Orleans, and that’s saying something. Mostly I’ve written short stories, the majority of which have never been published; only two have seen print, “Smalltown Boy” and “Son of a Preacher Man.”

I remember Michael McDowell from the 1980’s, when the horror boom was at its highest crest; I never read his work but I was aware of it. I remember reading the back covers of his Blackwater books and not being particularly interested in them; there was just something about them, and their Alabama setting, that somehow didn’t ring right to me; I don’t remember what or why, but I do remember picking them up several times in the bookstore, looking them over, and putting them back.

In recent years, McDowell has enjoyed a renaissance of sorts; he was a gay man who died from AIDS-related complications in 1999. I wasn’t aware that he was part of the writing team who published a gay mystery series under the name Nathan Aldyne until sometime in the last few years, and I’d been meaning to get around to finally read one of his horror novels, the reissue of The Elementals (which included an introduction by my friend, the novelist Michael Rowe–whose novels Enter, Night and Wild Fell are quite extraordinary)–which again is set in Alabama, only this time Mobile and the lower panhandle of Alabama that sits on either side of Mobile Bay (the same area, in fact, where I set my novel Dark Tide, only my novel was set on the other side of the bay). My friend Katrina Niidas Holm recently asked me to read the book so we could discuss it drunkenly over cocktails at Bouchercon in Toronto later this month; this morning I sat down and read it through. (It’s not very long; 218 pages in total.)

In the middle of a desolate Wednesday afternoon in the last sweltering days of May, a handful of mourners were gathered in the church dedicated to St. Jude Thaddeus in Mobile, Alabama. The air conditioning in the small sanctuary sometimes covered the noise of traffic at the intersection outside, but it occasionally did not, and the strident honking of an automobile horn ould sound above the organ music like a mutilated stop. The space was dim, damply cool, and stank of refrigerated flowers. Two dozen enormous and very expensive arrangements had been set in converging lines behind the altar. A massive blanket of silver roses lay draped across the light-blue casket, and there were petals scattered over the white satin interior. In the coffin was the body of a woman no more than fifty-five. Her features were squarish and set; the lines that ran from the corners of her mouth to her jaw were deep-plowed. Marian Savage had not been overtaken happily.

In the pew to the left of the coffin sat Dauphin Savage, the corpse’s surviving son. He wore a dark blue suit that fit tightly over last season’s frame, and a black silk band was fastened to his arm rather in imitation of a tourniquet. On his right, in a black dress and a black veil. was his wife Leigh. Leigh lifted her chin to catch sight of her dead mother-in-law’s profile in the blue coffin. Dauphin and Leigh would inherit almost everything.

Big Barbara McCray–Leigh’s mother and the corpse’s best friend–sat in the pew directly behind and wept audibly. Her black silk dress whined against the polished oaken pew as she twisted in her grief. Beside her, rolling his eyes in exasperation at his mother’s carrying-on, was Luker McCray. Luker’s opinion of the dead woman was that he had never seen her to better advantage than in her coffin. Next to Luker was his daughter, India, a girl of thirteen who had not known the dead woman in life. India interested herself in the church’s ornamental hangings, with an eye toward reproducing them in a needlepoint border.

On the other side of the central aisle sat the corpse’s only daughter, a nun. Sister Mary-Scot did not weep, but now and then the others heard the faint clack of her rosary beads against the wooden pew. Several pews behind the nun sat Odessa Red, a thin, grim black woman who had been three decades in the dead woman’s employ. Odessa wore a tiny blue velvet hat with a single feather dyed in India ink.

Before the funeral began, Big Barbara McCray had poked her daughter, and demanded of her why there was no printed order of service. Leigh shrugged. “Dauphin said do it that way. Less trouble for everybody so I didn’t say anything.”

This is an auspicious beginning to a novel that straddles the line between Southern Gothic and horror; but in using the word horror I am thinking of the quiet kind of horror, the kind Shirley Jackson wrote; this isn’t the kind where blood splatters and body parts go flying or you can hear the knife slicing through flesh and bone. This is the kind of horror that creeps up on you slowly, building in intensity and suspense until you are flipping the pages anxiously to find out what happens next.

McDowell introduces all of his characters in those few short sentences; Dauphin and his wife, Leigh; her mother Big Barbara; her brother Luker and her niece, India. Odessa also has a part to play in this story, and the only other character who doesn’t appear in this opening is Big Barbara’s estranged husband, Lawton. Lawton, like Mary-Scot, only plays a very small part in this tale, and so the reader doesn’t need to meet him until later.

(I do want to talk about character names here; the Savage family all have names that have something to do with Mary Queen of Scots; the deceased is Marian, her long dead husband Bothwell; Mary-Scot is as plain a reference as can be, whereas her two brothers were Mary Stuart’s husbands: Dauphin–her first husband was Dauphin Francois, later King Francois I of France–and the deceased elder brother, Darnley; the romantic Queen’s second husband was Lord Darnley. Marian’s –of Mary–deceased husband Bothwell bore the name of the Scottish Queen’s third husband, the Earl of Bothwell. These Savage men died in reverse order of the Queen’s husband’s though; Bothwell first followed by Darnley, and of course, as the only one living, Dauphin will die last. Also, there’s never any explanation for why Big Barbara is called Big Barbara; usually in Southern families the reason you would call someone “Big” is because there is a “Little;” there is no Little Barbara in this story, and I’m not sure where Luker came from as a name, either. I wondered if it was a colloquial pronunciation; names and words that end in an uh sound turn into ‘er’ in Alabama; Beulah being pronounced Beuler, for example, so I wondered if his name was Luka…)

The McCrays and the Savages are families bound by decades of friendship and now marriage; they have three identical houses on a southern spit of land in the lower, western side of the Alabama panhandle in a place called Beldame; Beldame is very remote, bounded by the Gulf on one side and a lagoon on the other; during high tide the gulf flows through a channel into the lagoon and turns Beldame into an island. There are no phones there nor power lines; electricity is provided by a generator and there is no air conditioning. Oh, how I remember those Alabama summers without air conditioning! One of the three houses is being lost to a drifting sand dune and is abandoned…and as the days pass, the reader begins to realize there’s something not right about that dune…or about that house.

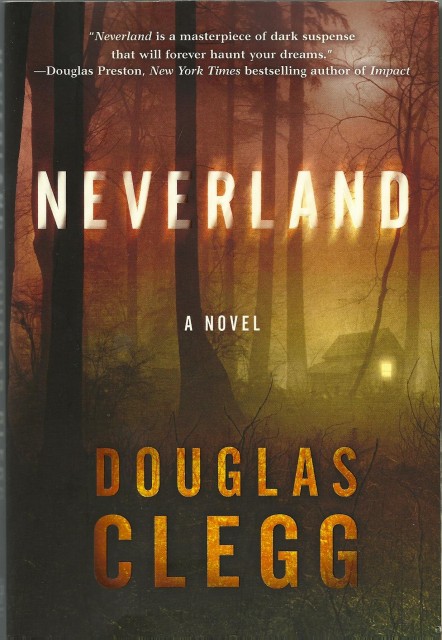

The book reminded me some of Douglas Clegg’s brilliant Neverland; that sense of those sticky hot summers in the South, visiting a place you’re not familiar with and is kind of foreign (the primary POV once the story moves to Beldame is India, who has never been there before); those afternoons where the heat and humidity make even breathing exhausting, the white sugary sand and the glare from it, lying in a shaded hammock just hoping for a breeze–the sudden rains and drops in temperature, where eighty degrees seems cold after days of it being over a hundred…the sense of place is very strong in this book, and Beldame is, like Hill House, what Stephen King called in his brilliant treatise on the genre Danse Macabre, ‘the bad place.”

I really enjoyed this book. A lot. And it has made me think about writing about Alabama again; this entire year I’ve been thinking that, and now feel like it’s a sign that maybe I should.

And now back to the spice mines.