I love Stephen King, and have since I first read Carrie when I was thirteen.

I will also go out on a limb and say that while he has written some amazing fiction and novels in the last forty years, the run of novels between (and including) Carrie and Misery in the 1970s and 1980’s was probably one of the greatest runs of incomparable work ever accomplished by any writer in any sub-genre or genre of fiction, period. There wasn’t a single stinker in that run, and even the one I personally dislike ( Pet Sematary) isn’t bad–it’s actually a testament to King’s skill that I’ve refused to reread it since that first time; it made me incredibly uncomfortable in so many ways viscerally that I’ve really never wanted to read it again.

And isn’t that the real point behind horror?

I also saw something recently about how people who suffer from anxiety often rewatch movies/television shows and reread books when they are anxious because there’s comfort in knowing how something ends. It had never occurred to me that this was a thing, but I used to reread books all the time when I was younger, often picking one up and just opening it at random and diving into the story again. I reread most of the earlier Stephen King novels countless times, as I have also reread books like Gone with the Wind and kids’ series books and other particular favorites. I still reread some periodically, like Rebecca and The Haunting of Hill House. When I picked up The Dead Zone to reread it–I realized that I don’t really reread the way I used to when I was younger. On the rare occasions when I thought about it, I figured it was because I don’t have the time and there are so many unread books around the house that I shouldn’t revisit something when I have unread books collecting dust and moldering on the shelves. But reading that about people with anxiety made me recognize myself and I also realized that I don’t reread as much as I used to (or rewatch) because I don’t have as much anxiety as I did when I was younger. (Don’t get me wrong, I still have too much of it for me to be comfortable going forward without doing something for it, you know.)

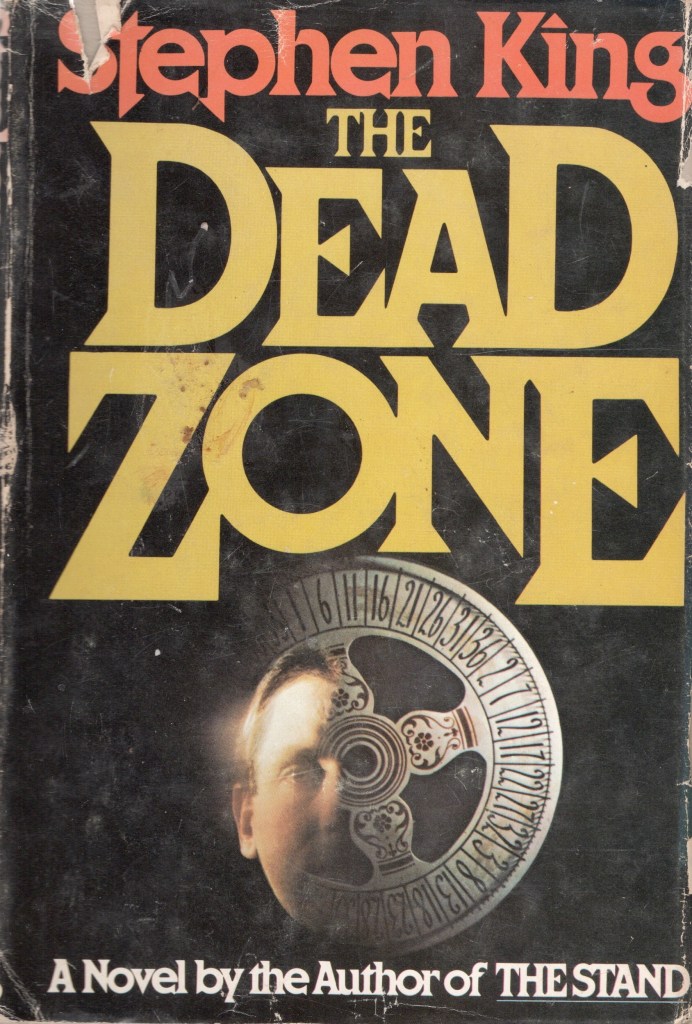

I’d thought about rereading The Dead Zone in the wake of the 2016 election; I had posted on social media early on during that campaign season, “Is anyone else reminded of Greg Stillson?” But I couldn’t, just as I couldn’t go back and revisit Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here or The Handmaid’s Tale or any of the other great collapse of American democracy novels. But this reread…made me truly appreciate all over again what a literary genius Stephen King actually is–and an American treasure.

By the time he graduated from college, John Smith had forgotten all about the bad fall he took on the ice that January day in 1953. In fact, he would have been hard put to remember it by the time he graduated from grammar school. And his mother and father never knew about it at all.

They were skating on a cleared patch of Runaround Pond in Durham. The bigger boys were playing hockey with old taped sticks and using a couple of potato baskets for goals/ The little kids were just farting around the way little kids had done since time immemorial–their ankles bowing comically in and out, their breath puffing in the frosty twenty degree air. At one corner of the cleared ice two rubber tires burned sootily, and a few parents sat nearby, watching their children. The age of the snowmobile ws still distant and winter fun still consisted of exercising your body rather than a gasoline engine.

Johnny had walked down from his house, just over the Pownal line, with his skates hung over his shoulder. AT six, he was a pretty fair skater. Not good enough to join in the big kids’ hockey games yet, but able to skate rings around most of the other first-graders, who were always pinwheeling their arms for balance or sprawling on their butts.

Now he skated slowly aruond the outer edge of the clear patch, wishing he could go backward like Timmy Benedix, listening to the ice thud and crackle mysteriously under the snow cover farther out, also listening to the shouts of the hockey players, the rumble of a pulp truck crossing the bridges on its way to U. S. Gypsum in Lisbon Falls, the murmur of conversation from the adults. He was very glad to be alive on this fair, winter day. Nothing was wrong with him, nothing troubled his mind, he wanted nothing…except to be able to skate backward, like Timmy Benedix.

So begins the prologue to The Dead Zone, a King classic that doesn’t get nearly the respect it probably should–especially in wake of the 2016 election. Johnny does, in fact, learn how to skate backwards, but is so excited about it he doesn’t notice he is heading right into the hockey game, where he gets hit broadside by a teenager and sent sprawling, hitting his head on the ice and knocking himself out. As he slowly comes back to consciousness, he starts muttering things that make no sense to the worried kids and adults gathered around him, including saying to “stop charging it’ll blow up”. But then he wakes up, is fine, goes home and doesn’t even tell his parents what happened (imagine a child knocking himself out and the parents not even being told today–never happen). A few days later one of the men’s car battery is dead, he jumps it–and it blows up in his face; only no one remembers the things Johnny was muttering; everyone’s forgotten about it.

The second part of the prologue introduces us to the other main character of the book, or the person who is fated to have the biggest impact on John’s existence, which also begs the question of fate and destiny; these two men’s lives are going to intersect, and the rest of the book follows their lives–primarily focused on Johnny’s, with the occasional swing over to see what’s going on with Greg Stillson and his climb to power and success. That prologue introduction to the traveling Bible salesman in Oklahoma who kicks a dog to death lets us know who he is right from the very start–he’s the bad guy, the reason all these things are happening to Johnny so their lives will cross.

Johnny’s story has three acts: first, the car accident that leaves him in a coma for five years (and introduces us to him, his love interest Sarah, and his parents) and inevitably ends with him catching the Castle Rock Strangler, using the abilities that he woke up from the coma with; the second, which concludes with the vision about the graduation party ending in fire and mass death; and the third, where he realizes he is the only person who can stop Stillson’s political rise, the country’s descent into fascism and a final cataclysmic nuclear war (which was an every day reality for us all back when this book was written, by the way).

The most interesting character to me, always, from the story of The Trojan War (I loved mythology and ancient history as a child) was Cassandra, the princess who was given the gift of prophecy accidentally (her ears were licked by one of Apollo’s temple snakes; he cursed her by having no one believe her and this frustration drove her mad); I always wanted to write from her perspective. John Smith is a modern-day Cassandra, a young man who unwillingly was given the gift to see the future as well as have psychic visions, and his story plays out very similarly to Cassandra’s, and asks the big question: if you had the knowledge and foresight to stop Hitler in 1932, even if it meant killing him, would you do it? The personal good vs. the collective good?

I thoroughly enjoyed this reread, and it definitely holds up, even if it is a time capsule of the 1970s, which also made it a big more fun.

(Oh, and that fall he took as a child? While it is never really explained where his abilities come from, King implies that that first head injury awakened the talent in him; the later head injury and coma woke it up again and gave it more power.)