As Constant Reader is aware–because I am nothing if not repetitious–I spent ages two to nineteen in the midwest, and the last five of those in rural Kansas. I’ve blogged endlessly about it, have written several books set there, and often blame (some of) my emotional scarring on the experience. It’s one of the reasons that stupid fucking song from earlier this year (“Try That in a Small Town”) was so ridiculous and offensive; yet another tired round of ammunition from people who equate cities with evil and rural life with purity and goodness–to which I always say “Someone’s never read Peyton Place, let alone lived in a small fucking town.” Big cities certainly don’t corner the market on crime and sin and lawlessness; small rural communities can be just as vile and horrible as any metropolis.

Shirley Jackson didn’t set “The Lottery” in Times Square for a reason.

There’s an entire essay to be written about the moral rot of the Bible Belt and rural America–and make no mistake, rural America is every bit as corrupt, sinfully evil, and dangerous as the worst neighborhood in any big city–but this is not the time, as I am here to talk about this marvelous novel I read very quickly last night.

“Can you see me?” Cole yelled over to them. He was standing on the south shore of the reservoir, barefoot and facing the water. He looked like he was thinking, but Janet knew better. The scrunch in Cole’s expression came from trying to keep his belly in a six-pack.

“I’ve got you,” Victoria yelled back as she framed her brother. She was using his phone and struggling with the device. “How do you zoom on this thing?” she asked as she shuffled to the edge, not looking at her feet and focusing on Cole. Janet could see a pink stamp of tongue at the corner of Victoria’s mouth as she tried her best to get the shot her brother wanted.

“You’ve got to be in portrait mode when you go live.”

Janet meant it as a polite pointer, but as the words came out of her mouth, they sounded like a dig. SHe didn’t mean it to be a dig, but she couldn’t help it, either. Her tone was why people thought she was such a bitch. Her tone and that she kind of was. Whatever–it was fun to watch the sheep quiver.

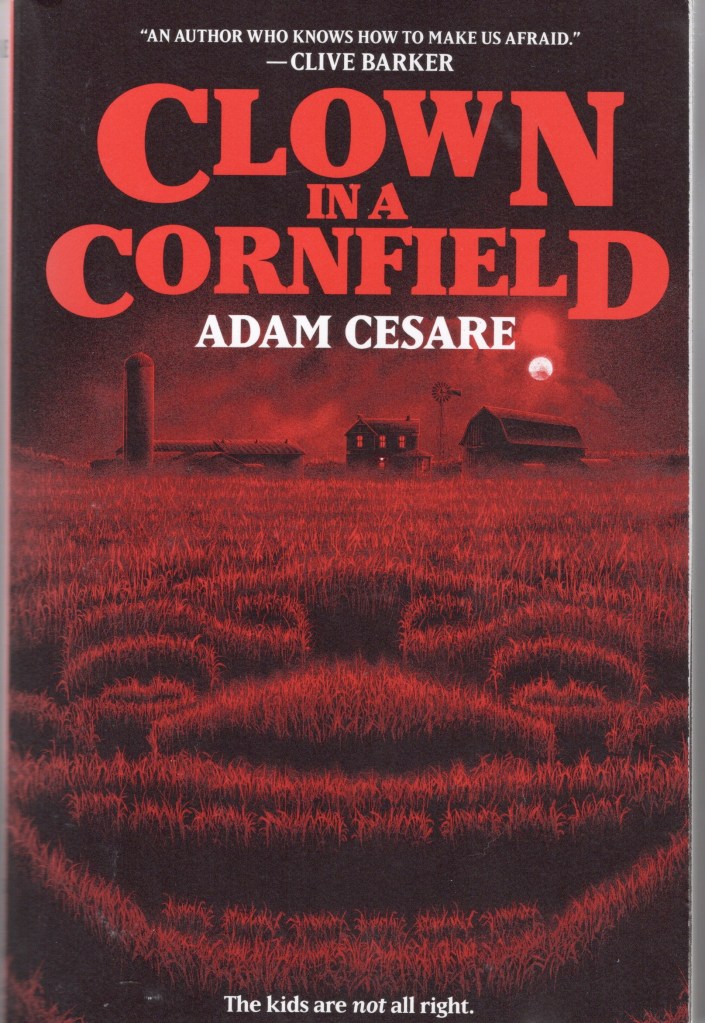

I don’t remember how Adam Cesare and his y/a horror thriller Clown in a Cornfield first came to my attention; if it was a suggestion from a website or if I saw someone talking about it on social media or I don’t know where, but I am very glad it did. The book is absolutely right up my alley–young adults, horror, small town Midwestern America (you know, “the REAL America,” right, Sarah Palin?), and terrifying clowns. I’ve never been afraid of clowns–although many people are, and I can respect that. The white greasepaint, the garish hair and eye make-up, the clothes–it’s not hard to see how something intended to entertain children (remember, fairy tales in their original form are horrifying) can easily become something that is absolutely terrifying. John Wayne Gacy, notorious serial killer who preyed on children, worked as a clown for kids’ parties–which is very unsettling, and of course, who can ever forget Stephen King’s masterclass of clown horror, It? Killer clowns have become kind of a cliché…but they still work.

Clown in a Cornfield works on its basic surface level–it’s a scary story that reads quickly and raises the adrenaline and is chockfull of surprises and twists; like the novel version of a slasher movie. (Something I’ve always wanted to do, frankly.) It takes place over the course of a couple of days, and is set in the small dying town of Kettle Springs, Missouri, where main character Quinn Maybrook and her father have just moved from Philadelphia; it’s hinted early on that the tragic death of her mother is why they moved during her senior year: a fresh start in a wholesome rural small town in the REAL America…which turns out to be all too real. The town is dying because the corn syrup processing plant shut down, and the town is losing population. The above few paragraphs are from the prologue–which sets up the rest of the book. There’s a tragic death at the reservoir that day, which changes the kids and changes the town–as though they’ve finally crossed a line they were dancing very close to the edge of and there isn’t any turning back.

The willful and wild teens of the town have planned a surprise during the Founders’ Day parade which Quinn witnesses when the prank goes haywire, and she learns there’s a lot of anger directed at the town’s teenagers–the kids from above who have a Youtube channel where they film themselves playing pranks on people around town–and the idea is that the pranks have become dangerous and the kids are out of control. The next night there’s a party out in a cornfield, and that’s when the corn syrup company’s mascot, Frendo the Clown, shows up with a crossbow and the body count starts to rise.

I really enjoyed this book. It was well written and works very well on all of its multiple layers, from the basic story which is well paced and exciting, to the layers of social critique, satire, and politics that it also manages to be. I found myself caring about the main characters and rooting for them, and while I saw one major surprise coming way ahead of time, there were a lot of other shocks and surprises along the way that made up for the telegraphing.

There’s also a sequel now, and I am looking forward to the second installment. I think you’ll like it, too, Constant Reader, so give it a whirl–thank me later.