When I wrote the introduction to Night Shadows: Queer Horror, I talked about the similarities between crime fiction and horror, as a means to explain how two crime writers (myself and the incomparable J. M. Redmann) found ourselves editing a horror anthology. Make no mistake; there are a lot of similarities between the two genres. Both, for example, are concerned with death and to no less a degree justice; there’s almost always a mystery involved in a horror novel–primarily as the main characters try to figure out what is going on and what they can do about it, but still. So-called slasher films/novels are really just the horror equivalent of serial killer stories; The Silence of the Lambs notably was both crime and horror. I’ve always been interested in both, although I lean more to the crime side, since I really don’t have the imagination or creativity to write horror (or much of it, anyway; and everything I do write that is horror is undoubtedly horribly derivative).

The book I just finished reading, Dan Chaon’s Ill Will, manages to blur the line between horror and dark crime fiction as well. It is, in fact, one of the creepiest and darkest things I’ve ever read; definitely in the top ten, at the very least.

Sometimes in the first days of November the body of the young man who had disappeared sank to the bottom of the river. Facedown, bumping lightly against the muddy bed below the flowing water, the body was probably carried for several miles–frowning with gentle surprise, arms held a little away from his sides, legs stiff. The underwater plants ran their fronds along the feathered headdress the boy was wearing, across the boy’s forehead and war-paint stripes and lips, down across the fringed buckskin shirt and wolf-tooth necklace, across loincloth and deerskin leggings, tracing the feet in their moccasins. The fish and other scavengers were most asleep during this period. The body bumped against rocks and branches, scraped along gravel, but it was mostly preserved. In April, when the two freshman college girls saw the boy’s face under the thin layer of ice among the reeds and cattails at the edge of the old skating pond, they at first imagined the corpse was a discarded mannequin or a plastic Halloween mask. They were collecting pond-water specimens for their biology course, and both of them were feeling scientific rather than superstitious, and one of the girls reached down and touched the face’s cheek with the eraser tip of her pencil.

During this same period of months, November through April, Dustin Tillman had been drifting along his own trajectory. He was forty-one years old, married with two teenage sons, a psychologist with a small practice and formerly, he sometimes told people, some occasional forays into forensics. His life, he thought, was a collection of the usual stuff: driving to and from work, listening to the radio, checking and answering his steadily accumulating email, shopping at the supermarket, and watching select highly regarded news on television and reading a few books that had been well received and helping the boys with their homework, details that were–he was increasingly aware–units of measurement by which he was parceling out his life.

When his cousin Kate called him, later that week after the body was found, he was already feeling a lot of vague anxiety. He was having a hard time about his upcoming birthday, which, he realized, seemed like a very bourgeois and mundane thing to worry about. He had recently quit smoking, so there was that, too. Without nicotine, his brain seemed murky with circling, unfocused dread, and the world itself appeared somehow more unfriendly–emanating, he couldn’t help but think, a soft glow of ill will.

The book is about, ultimately, damage: how violent crime and trauma affects people, and how that damage can be passed along to the next generation.

When Dustin was a child, his parents, along with his aunt and uncle (two brothers married two sisters) were murdered while the kids slept outside the house in a camper, the night before they were all due to leave for Yellowstone. The blame fell on Dustin’s older, adopted brother, Rusty–in no small part to Dustin’s testimony and that of his older cousin, Kate–who claimed to have resurfaced memories of Rusty forcing them to participate in Satanic rituals (this was actually a big thing in the 1980’s), and Rusty was convicted and went to jail. Recently, DNA evidence over-turned Rusty’s conviction, and he was released. Dustin’s wife has recently died of cancer, and his youngest son Aaron is using heroin while pretending to go to college. And one of Dustin’s patients, a former cop, is convinced that young college boys are being kidnapped and ritualistically drowned by a cult of some sort, and wants Dustin to help him look into it. All of these disparate threads weave in and out of each other; interconnected yet causing more alienation for this complex and completely dysfunctional family as the book careens along to its ultimate denouement, a downward spiral of hopelessness and tragedy.

The writing is spectacular, and Chaon also plays with form and even typesetting to get the feel of the novel across to the reader; this can seem intrusive and distracting at times, but as you continue to read, this style creates an irresistible mood and drive to continue reading; as the Tillmans’ past, present, and future all seem to converge in on their lives and each other, it becomes almost hypnotic.

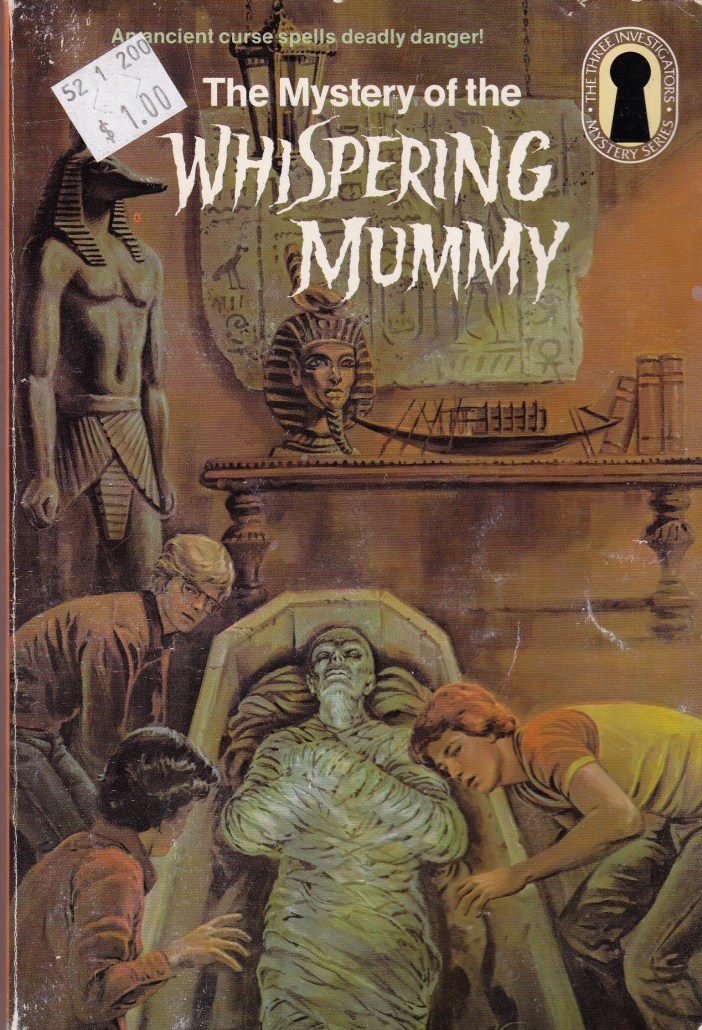

There’s also a shout out to The Three Investigators in the text, which I also loved.

This book is amazing. It reminded somewhat of Lou Berney’s The Long and Faraway Gone, which was sublime and one of the best novels I’ve read over the past few years. I highly recommend this…and can’t wait to read more of Chaon’s work.