Sunday morning. Yesterday wasn’t nearly as productive as I would have hoped; but I am pleased to report that “My Brother’s Keeper” is finished, and “Don’t Look Down” isn’t nearly as big of a mess as I thought it was before reading it from beginning to end. It needs some serious polishing before I can consider it to be done–or read it aloud–but I think another push on it today and it will be done. I also started writing yet another story yesterday–“This Thing of Darkness”–which is kind of an interesting idea. We’ll see how it goes. My goal for today is to finish “Don’t Look Down” and “Fireflies” today so they are ready for the read-aloud. And, of course, once “Don’t Look Down” is finished, my collection will be as well–which is kind of exciting.

I didn’t work on Scotty yesterday; I am going to hold off on going back to work on him until tomorrow. I want to get this collection finished, and he needs to sit for another day. I may go back and reread what I’ve already written; the first fourteen chapters, so I can figure out where, precisely, this next chapter needs to go.

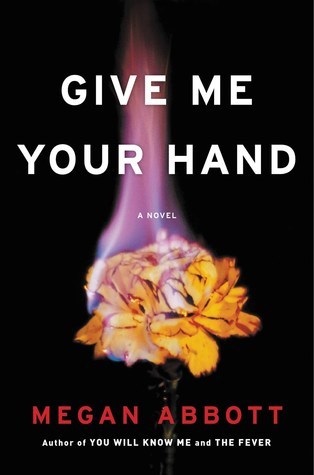

I also finished reading Megan Abbott’s amazing Give Me Your Hand last night.

I guess I always knew, in some subterranean way, Diane and I would end up back together.

We were bound, ankle to ankle, a monstrous three-legged race.

Accidental accomplices. Wary conspirators.

Or Siamese twins, fused in some hidden place.

It is powerful, this thing we share. A murky history, its narrative near impenetrable. We keep telling it to ourselves, noting its twists and turns, trying to make sense of it. And hiding it from everyone else.

Sometimes it feels like Diane was a corner of myself broken off and left to roam my body, floating through my blood.

On occasional nights, stumbling to the bathroom after a bad dream, a Diane dream, I avoid the mirror, averting my eyes, leaving the light off, some primitive part of my half-asleep brain certain that if I looked, she might be there. (Cover your mirrors after dark, my great-grandma used to say. Or they trap the dreamer’s wandering soul.)

Megan Abbott has been a favorite of mine, since years ago when I first read Bury Me Deep as a judge for the Hammett Prize. A period noir, set in the early 1980’s and based on a true story, I was blown away by its deceptive simplicity and hidden complexities. It echoed of the great noirs of James M. Cain and great hardboiled women writers, like Margaret Millar and Dorothy B. Hughes; a tale of desperation and love and murder, crime and ruined reputations, as it delved into the complex emotions that could lead a woman to commit a horrifically brutal murder; its exploration of small-town corruption was reminiscent of Hammett’s Red Harvest. Over the years since that first reading, I’ve gone on to read Abbott’s other brilliances: This Song is You, Queenpin, Dare Me, The End of Everything, You Will Know Me. Her women aren’t victims in the classic sense of victims in crime fiction; her women have agency, they make their decisions and they know their own power; a common theme to all of her novels is the discovery of that power and learning to harness it; whether it’s sexual power (The End of Everything), physical power (You Will Know Me), cerebral (Give Me Your Hand), or inner strength (Dare Me).

And somehow, she manages to continue to grow and get better as a novelist, as a writer, with every book.

She is probably the greatest psychological suspense writer of our time; her ability to create complex inner lives for her characters, to explore the duality of weakness and strength we all carry within us, and the delving into the complicated nuances of female friendships, with all their inner rivalries and passions and jealousies and affections, is probably unparalleled. Her books are also incredibly smart and layered; this one has references, both subtle and overt, to both Hamlet and Macbeth seamlessly woven into the text; the dual, competing themes of inertia despite the knowledge of a crime versus unfettered ambition; and what to do when faced with both. How do you decide? And what does your decisions say about you as a person?

Give Me Your Hand is set in the world of research science, which may seem a weird setting for a crime novel…but competition for research funding and positions, for advancement in career, the thin veneer of civility and camaraderie between co-workers angling for plum research assignments, is at its very heart, noir. One of the characters, Alex, says at one point, jokingly, “we’re a nest of vipers”…and it turns out to be very true.

The novel follows the complex friendship between the main character, Kit Owens and Diane Fleming, who first meet as young teens at Science Camp, and again later their senior year of high school. They become friends, with similar interests; Kit and Diane push each other to be their very best. It is the friendship with Diane that sets Kit on the road to her career as a research scientist; yet their friendship is blown apart by a secret Diane shares with Kit, and the knowledge of that shared secret haunts both women for the rest of their lives. Their paths cross again years later, working in the same lab and competing for a limited number of spots on a new, important research project having to do with how excessive premenstrual syndrome: premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The book also offers two timelines: the senior year, with its heavy influence of the Hamlet theme, and the present, which is more on the lines of Macbeth. Blood also is used, repeatedly, brilliantly, as an image; the study is on a disorder caused by menstruation, and of course, blood as in relatives, as a life-force, as a motivator.

The book is slated for a July release; usually when I get advance copies I wait until the release date is imminent for me to blog about these books. But this one couldn’t wait; I’ve not been able to stop thinking about it since finishing it late last night.

Preorder the hell out of this, people.