I am often, incorrectly, referred to as a “New Orleans expert.”

Nothing, as I inferred in that sentence, could be further than the truth.

Don’t get me wrong–I absolutely, positively love New Orleans, for many and varied reasons. The short, elevator-pitch answer is always Because I’m not the weird one here. And it’s true; New Orleans is an eccentric city filled with eccentrics. No other city in North America is like it, even remotely; New Orleans is a city that doesn’t abhor strangeness, but rather embraces it. When I came here for my thirty-third birthday in 1994, when I got out of the cab at the intersection of St. Ann and Bourbon that first night, my actual birthday, to go out to the gay bars of the Quarter, I knew I was home. There was no doubt in my mind, no question; just an immediate and instant connection with the city and I knew, not only that I would eventually live here, but that if and when I did all my dreams would come true.

And that feeling was right. I fell in love with New Orleans, I fell in love in New Orleans, and after I moved here, all of my dreams did, in fact, come true.

So, when I write about New Orleans my deep and abiding love and passion for the city inevitably comes through. But I always kind of smile inwardly to myself when people call me an expert on the city; I am hardly that, and libraries could be filled with what I don’t know about the city. Sure, I do know some things, but an expert? Not even remotely close.

A perfect case in point is Milneburg. What, you may every well ask, is Milneburg? Milneburg was a resort village on the lake shore that many New Orleanians would escape to during the wretched heat of the summer (and I am vastly oversimplifying this); I’ve read about it in history books and so forth. I even thought Murder in Milneburg might make for an interesting historical mystery. I always saw it, though, in my mind’s eye, as close to the parish line between Orleans and Jefferson parishes; closer to Metairie and the causeway. So, you can imagine my shock when I saw a map of Milneburg posted on one of the New Orleans historical Facebook pages I belong to, and realized that I was completely wrong: there was a railroad line from New Orleans to Milneburg (which I knew) that ran along what is now Elysian Fields Avenue.

So, Milneburg was actually where the University of New Orleans is now located; and the train line continued along east, crossing at the Rigolets.

Some New Orleans expert I am, which is why I decided to start reading more histories of the city over the last few years. It’s been quite an education, and there are still some things I don’t quite grasp–like when the Basin Canal was filled in to become Basin Street, and what relation that had to Storyville and Treme, because the train station also used to be located near Storyville (this was part of the reason why the drive to clean up Storyville and end legal prostitution in New Orleans was successful; the other part was because New Orleans was an embarkation point for the military during World War I and the Pentagon frowned on delivering green military recruits to whorehouses).

So, yeah, some expert I am.

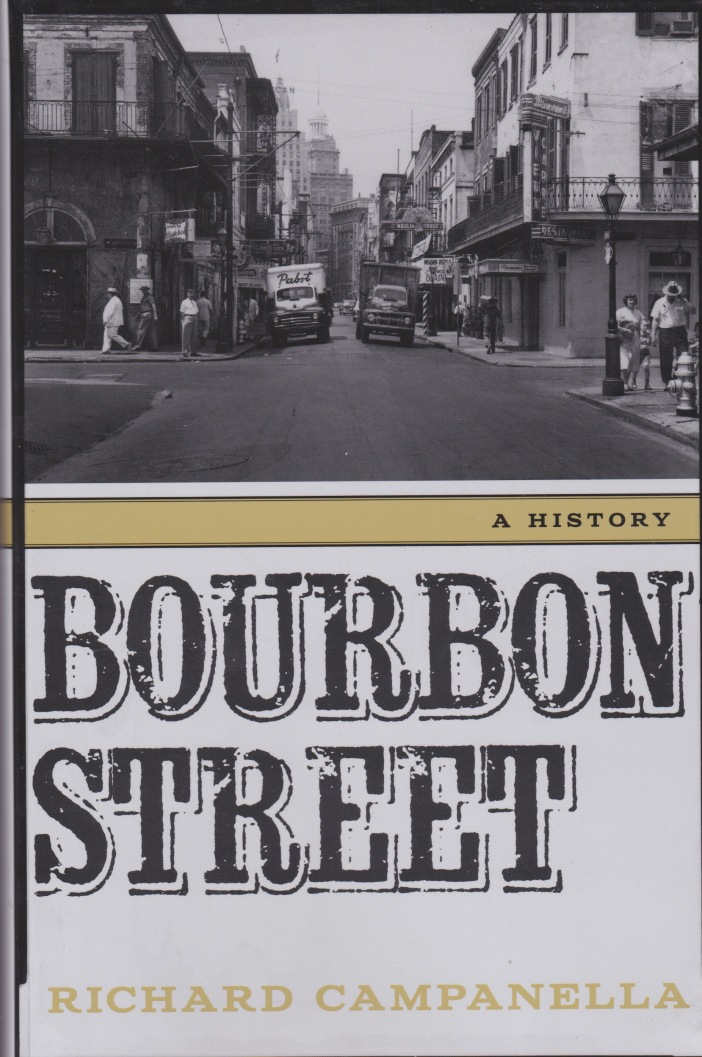

But I really enjoyed Richard Campanella’s Bourbon Street.

There are no straight lines in nature. Nor are there any right angles. Rather, intricate arcs and fractures merge and bifurcate recurrently, like capillaries in a plant leaf or veins in an arm. Nowhere is this sinuous geometry more evident than in deltas, like that of the Mississippi River. Starting eighteen thousand years ago, warming global temperatures melted immense ice sheets across North America. The runoff aggregated to form the lower Mississippi River and flowed southward bearing vast quantities of sediment. The bluffs and terraces that confined the channel to a broad alluvial valley petered out roughly between present-day Lafayette and Baton Rouge in Louisiana, south of which lay the Gulf of Mexico.

Into that sea disembogued the Mississippi, its innumerable tons of alluvium smothering the soft marshes of the Gulf Coast and accumulating upon the hard clays of the sea floor. So voluminous was the Mississippi’s muddy water column that it overpowered the (relatively weak tides and currents of) Gulf of Mexico, thus prograding the deposition farther into the sea. Occasional crevasses in the river’s banks diverted waters to the left or right, creating multiple river mouths and thus multiple depositions. High springtime flow also overtopped the river’s banks and released a think sheet of sediment-laden water sideways, further raising the delta’s elevation.

In this manner, southeastern Louisiana rose from the sea. The process took about 7,200 years, making the Mississippi Delta, as Mark Twain put it, “the youthfulest batch of country that lies around there anywhere.” Young, dynamic, fluid, warm, humid: flora and fauna flourish in such conditions, as evidenced by the verdant vegetation and high productivity of the delta’s ecosystem. Humans, on the other other, view these same conditons as inhospitable, dangerous, even evil, and endeavor to impose rigidity and rectitude upon them, so as to better exploit the delta’s resources.

If New Orleans is known for anything, it’s Bourbon Street. Everyone has heard about Bourbon Street, it seems; just as they’ve heard about Carnival/Mardi Gras, beads, and show us your tits (which locals do NOT do–either yell it or bare them). Campanella’s book traces the history of the famous street, and by extension, the French Quarter itself, from its very beginnings when the French arrived and designed the streets, to its modern day incarnation as a street of endless partying and no little debauchery. It’s very well researched, and Campanella, who I believe teaches at Tulane, is the true expert on the city; I follow his pages on Facebook, and I can’t even begin to tell you how much inspiration and information Bourbon Street has given me. I’ve put so many page markers in my copy that I’m worried about breaking the spine!

One thing that my reading of New Orleans history has further emphasized to me–and it also really comes through strongly in Campanella’s book–is how New Orleans has always been a city of neighborhoods, and how each neighborhood of the city had (has?) its own unique sense of itself, and how those who lived in those neighborhoods so strongly identified with them. The evolution of the French Quarter from the original city and seat of its government, to the original French leaving and being replaced by immigrants (as late as the 1960’s the lower quarter was known as ‘little Sicily’ because of all the Italian immigrants and their descendants who lived there), and then evolved again into a different type of neighborhood, with mixed incomes and everything from inexpensive apartments to gradiose condos; and a variety of ethnicities, races, sexualities, and gender identities.

One of the primary concerns modern-day New Orleanians have is the fear of the loss of those neighborhoods; because those neighborhoods were the incubators for all the things that makes New Orleans so special and unique: the music, the art, the literature, and the characters. Short-term rentals are carving up neighborhoods and the rents/property values are currently climbing, with no peak in sight, and people are rightfully concerned about these things.

But one thing I’ve learned from reading these histories, and Campanella’s in particular, is that New Orleans has always changed and evolved, yet has also always managed to keep that unique strangeness that make it New Orleans somehow intact.

If you love New Orleans or find it at all interesting, I cannot recommend Bourbon Street enough to you.